Today is Dec 7. Growing up in the shadow of world war, you remembered and honored those days. Days like Armistice Day and Pearl Harbor. When done rightly, the honor fell upon those who risked and gave their lives to stop global tyranny. When done badly, the day could become a day of self-righteous preening and glorying in war.

Today is Dec 7. Growing up in the shadow of world war, you remembered and honored those days. Days like Armistice Day and Pearl Harbor. When done rightly, the honor fell upon those who risked and gave their lives to stop global tyranny. When done badly, the day could become a day of self-righteous preening and glorying in war.

But, however you celebrate, remember this: that every man and woman who came back from the Front carried forever in their minds terrible visions of carnage, loss, fear, cowardice and bravery. Less known, and even less discussed, many carried guilt, a deep unwashable guilt that civilians and family could never understand and mostly never knew.

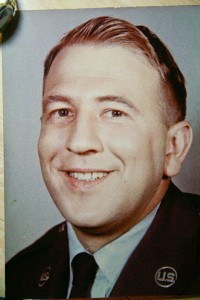

December 7, 1941 changed my father’s life in ways he could never have imagined or intended. He joined the Marines and met a kid from a small farm in California name Jack Matthews. Together they went to hell, known to the world as Guadalcanal. Jack never came back, though his name did. Five years later it became part of me. It is my middle name.

Every country sent youngsters like my dad and Jack into war and told them to violate every important moral rule they’d been raised by. They were boys–teenagers. They were now told they were required to kill, and to kill as many as they could, to hate the enemy, to be mass killers, if possible.

The ones who survived the war, came home and tried to forget how they killed, how they watched friends die, cut to pieces by machine gun fire or blown up by mortars, grenades, and bombs. Some felt guilty they survived. Some felt guilty for some act they believed was cowardly, whether it was or not.

But those in combat came home with blood on their hands that no one could see, almost no one could understand, and about which they were told to forget. And they did. Or tried.

My sister tells me that in the last weeks of my father’s life, he began to weep. He was not only not “religious,” he was oddly anti-religious. He couldn’t point to some awful church or pastor or priest or experience, he just didn’t want to have anything to do with “God.” (How ironic that two of his three children became clergy.) As he began to weep, he told Marilyn that God could never accept him for what he did in that terrible Pacific War that most of us have consigned to the dull past. “I did things,” he said. “Terrible things. I killed people.” God could never want me after all I did in the war.”

Today we know about PTSD. But, not then. Think. Remember. Remember your father. Was he in combat? Was he at times hurtful and violent toward you or others? Was he at times distant and unreachable? If so, it is possible he was still carrying that terrible war in his body and mind.

Forgive him. If he is alive, hug him. And hug him for me, for I never understood this when my father was alive, and I can’t hug him now.

And remember this every time someone tells you that it’s time to go to war.