When a big game is about to be played, it is fun to go online and scan for tickets, even if you don’t plan to attend. It is an effective way to see how the business of sports works, and it can be a pleasant reminder of how far short most of us have fallen from achieving the financial ranks of the One Percent. When the game in question is a Super Bowl, it also confirms what any viewer of ESPN can already tell you: it is truly the NFL’s world.

When a big game is about to be played, it is fun to go online and scan for tickets, even if you don’t plan to attend. It is an effective way to see how the business of sports works, and it can be a pleasant reminder of how far short most of us have fallen from achieving the financial ranks of the One Percent. When the game in question is a Super Bowl, it also confirms what any viewer of ESPN can already tell you: it is truly the NFL’s world.

To a far greater extent than other sports, the NFL reserves the in-person experience of its championship games to itself and its favored sponsors. Typically it distributes Super Bowl tickets as follows:

· 35% to the NFL teams playing in the game

· 5% to the host team

· 35% to the remaining NFL teams

· 25% to corporate sponsors and NFL charities

After players and team employees get their personal allotments, NFL team tickets go to season ticket holders, though membership in that exalted class does not guarantee receipt but only entry to a lottery for the rights to purchase them at face value, currently between $850 and $1,250. On average the odds of success for season ticket holders are about 1 in 10 if their team is playing in the game, and about 1 in 150 if not. Typically the NFL also reserves 500 tickets for a barely publicized lottery to which the general public can apply months before the game—also for the right to purchase at face value. It received about 30,000 entries to the lottery for this year’s game, which worked out to odds similar to those for the latter group of season ticket holders.

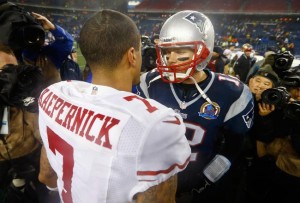

In other words, without knowing a privileged someone or figuring out the secret to winning lotteries, the only way to attend a Super Bowl is to submit to the free market and pay an officially sanctioned Internet scalper like Stub Hub. At the moment the cheapest tickets are $1,770 each, which is cheaper than last year when well-heeled New York fans drove up the cost of seeing the football Giants play the Patriots. It is almost double the market price from a few years ago, however, when the Colts played the Saints in Miami. It is also about double the price typical of championship games in baseball and basketball. The economy might be shaky elsewhere in the world, but it is alive and well in the NFL.

As if this pound of flesh was not enough to demand of dedicated but unconnected football fans, the practice of holding Super Bowls at pre-determined neutral sites forces them to hand over another pound to get to the game and find a place to stay once they arrive. Here also the NFL does its best to make life difficult. When it announces the city where a Super Bowl is to be played, generally three years prior to the event, it also immediately reserves 90 percent of the hotel rooms in the area for itself and its sponsors on that weekend at a favorably negotiated rate. For those not so fortunate to be covered by this arrangement, Super Bowl hotel rates can be several times the normal price. Combined with a typical minimum booking of four nights, a total expense of less than four figures for lodging can be considered a bargain. Flights and rental cars also come at a premium, though this can be mitigated somewhat by acting fast right after the conference championship games are over. A Priceline search last Monday produced fares of $1,056 and up to fly round-trip from San Francisco, about two and a half times the cost of a similar flight for a weekend later in the month. Since then the cheapest Super Bowl weekend flights from San Francisco have increased to almost $1,300. Similar markups are typical for rental cars, which are a necessity when your hotel might be fifty miles or more from the stadium.

Then again, I can easily anticipate reselling the tickets even in that circumstance and taking the sizeable profit instead, because I have already seen in person one of my favorite teams play for a championship. Above my office desk is my framed ticket for Game 4 of the 2002 World Series. My fondest memory of that experience wasn’t that the baseball Giants won their first home game in the Fall Classic in forty years, but that I got to see them do it virtually for free. I was already in the city for a conference, and my brother who works in the Financial District—bless his heart—incredibly managed to get tickets when someone in his office gave them away (he was a Dodger fan and couldn’t be bothered to use them). We got to the ballpark just as the jets flew overhead, and the only money I spent that evening was for the bratwurst and soda I gratefully bought for my brother and the gift shop souvenirs I took home to my wife and kids. I didn’t bother with a cab afterwards; I walked back to my hotel instead as happy as I’ve ever felt in my life. I’m not even sure that my feet touched the ground.