So imagine my surprise to find a section about bathing in Pierre Riche’s Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne. Carolingian princes took baths and changed their clothes once a week. OK, that’s not as often as Americans who can’t live without their daily showers, but it’s a lot more frequent than what I was led to believe.

Commoners would have bathed less often than aristocrats because of the time and labor it took to fill a tub, but they would have bathed as often as they could.

We can blame the misconception of medieval filthiness on the plague, or rather the belief about how the plague was spread in the 15th century—bad air that entered the body through the pores. Medical treatises of the time advised against frequent bathing, among other things, in order to keep the pores closed.

Go back to the Carolingians of the eighth and ninth centuries, and you’ll find a different attitude. Baths were a requirement for palaces, and bathhouses contained hot and cold pools. The bathhouse at the Charlemagne’s palace at Aachen (Aix-la-Chapelle in French) was spring fed and could accommodate up to 100 bathers.

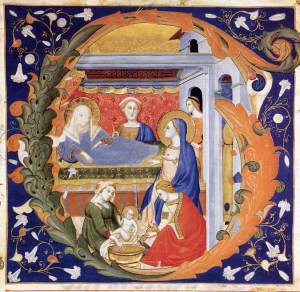

Abbeys also had baths for the residents, guests, and the sick. Yes, you read that last part right, the sick, who were allowed baths on a mostly regular basis. So much for bathing being bad for health. Frequent hair-washing in the winter was to be avoided, but that’s not exactly a surprise when you consider how cold it was indoors.

Some medieval people didn’t bathe, but the reason had nothing to do with health. Abstaining from the bath was a form of penance, just like giving up wine or meat or something else you enjoy.

Between baths, people of all classes would wash hands and face using basins of cold water. Just like most of us, medieval people wanted to be clean.

Sources

Daily Life in the World of Charlemagne, Pierre Riche, translated by Jo Ann McNamara

Daily Life in Medieval Times, Frances and Joseph Gies

Kim Rendfeld is the author of The Cross and the Dragon, a story a noblewoman contending with a vengeful jilted suitor and anxiety for her husband about to go to war, and The Ashes of Heaven’s Pillar, a tale about the lengths a Saxon peasant will go to protect her children. To read the first chapters of either novel or learn more about Kim, visit kimrendfeld.com. You’re also welcome to visit her blog Outtakes of a Historical Novelist at kimrendfeld.wordpress.com, like her on Facebook at facebook.com/authorkimrendfeld, or follow her on Twitter at @kimrendfeld, or contact her at kim [at] kimrendfeld [dot] com.