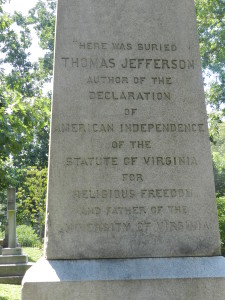

If I could choose any stone to have over my grave, my pick would be Thomas Jefferson’s. His is an obelisk, and his epitaph reads as follows:

HERE WAS BURIED THOMAS JEFFERSON AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE OF THE STATUTE OF VIRGINIA FOR RELIGIOUS FREEDOM AND FATHER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF VIRGINIA

This is as noteworthy for what it leaves out as well as for what it includes. Jefferson also was the third President of the United States, but somehow he did not think that important enough to list among his accomplishments. He may have thought, correctly, that the others were more than enough to guarantee his immortality.

Monticello did not have the intimidating grandeur of the Vanderbilts’ Biltmore mansion, which I had just toured, but otherwise it lived up to its reputation during my visit. It is kept in far better condition than in Jefferson’s day, mostly because the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has more reliable funding than the debt-burdened Jefferson. The house tour started in the front hall, where Jefferson displayed many of the Indian artifacts and other items he received from the Lewis and Clark expedition. It accomplished his intention to impress visitors with his knowledge of anthropology and geography. The other rooms that impressed me most were the parlor and his bedroom/study. Inside the parlor were some extraordinary paintings, including a large and prominently displayed image of Herodias holding the head of John the Baptist on a platter. Despite the stark nature of the image, the features of both Herodias and the head itself were portrayed with such a gentle softness as to make the scene almost tender. Considering that Jefferson, who was a Deist, was not particularly devoted to Christianity and its imagery, I wondered what led him to acquire the painting.

The bedroom/study, for its part, was a wonderful space. The study contained a lot of Jefferson’s contraptions, including a revolving stand that could hold five open books at once and a polygraph that would make duplicate copies of letters as Jefferson wrote them. The bed was set in an alcove between the two rooms, so Jefferson could roll out of bed in the mornings and sit at his desk a few feet away where he composed and read his voluminous correspondence. “That’s a short commute,” I said to the tour guide. The bedroom was also well-situated in another way, depending on your view of Jefferson’s personal life. It was the only bedroom on the first floor, and it was near an outside entrance, making it possible for his alleged mistress, Sally Hemings, to go in and out in the night without being observed.

The Jefferson Foundation and its Monticello staff are much more forthcoming on the subject of slavery than they used to be. In the past, it was not unusual for them to sanitize Jefferson’s records of any unsavory references to this part of his life, including whippings and sales of uncooperative slaves to distant plantations. In this, they acted in the spirit of Jefferson himself, who was conscious of his reputation and did much to conceal these details from antislavery friends who questioned him on the peculiar institution. At present, visits to Monticello include walking tours on slavery as it existed there in Jefferson’s time, including its unpleasant parts, and the staff explicitly leaves to visitors any judgment on what took place.

So also for Jefferson and his achievements as they read on his epitaph. Good deeds can be honored in the context of failings in other parts of life. They give us hope that sometimes we can be better than we normally are.