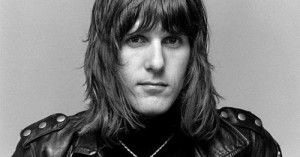

I was having a beer with a friend of mine when I got the news of Keith Emerson’s death. There seems to have been a recent wave of rock and roll icons exiting stage left – and given all of our advancing ages – more soon to come. But hearing about the untimely demise of my adolescent keyboard idol stopped me in my tracks with a wave of shock and sadness. I told my friend about this news and he replied, “Keith who?” Amongst the kindred musical souls of my youth, this clearly would have required no explanation, but it is easy to forget the rock and roll divide. For my brethren it is hard to comprehend that there is a large swath of people who ignored progressive rock, or relegated it to a stage of musical excess that needed to be overcome. In the recent HBO miniseries Vinyl, co-created by Martin Scorsese and Mick Jagger, there is a scene where the coked out record producer from the mid-seventies essentially screams for this. And the battle rages on…

I was having a beer with a friend of mine when I got the news of Keith Emerson’s death. There seems to have been a recent wave of rock and roll icons exiting stage left – and given all of our advancing ages – more soon to come. But hearing about the untimely demise of my adolescent keyboard idol stopped me in my tracks with a wave of shock and sadness. I told my friend about this news and he replied, “Keith who?” Amongst the kindred musical souls of my youth, this clearly would have required no explanation, but it is easy to forget the rock and roll divide. For my brethren it is hard to comprehend that there is a large swath of people who ignored progressive rock, or relegated it to a stage of musical excess that needed to be overcome. In the recent HBO miniseries Vinyl, co-created by Martin Scorsese and Mick Jagger, there is a scene where the coked out record producer from the mid-seventies essentially screams for this. And the battle rages on…

However, for us passionate aficionados of this music, (and there are many) in the best of this genre there was, and continues to be, a passion, intelligence, complex brilliance, and an authentic excitement that is rarely recaptured in contemporary music. And in his prime, Keith exemplified this. So I took a swig of my beer and tried to share with my uninitiated colleague what Mr. Emerson meant to me, particularly as a keyboard player growing up in the 70’s.

First, he was one of the early pioneers, and probably the best, at making classical music accessible and fun to a rock and rock mainstream audience. Although by the time I was exposed to ELP in my early adolescence I had already been playing classical piano for some time, hearing “Pictures at an Exhibition” really turned me on to want to seek out the original Mussorgsky. I found the piano works and gleefully stumbled my way through them. The same was true for his powerful adaptations of Copeland’s “Hoedown” and “Fanfare for the Common Man” and the use of Prokofiev in “Father Christmas.” As recently as a few days ago I was playing with the Bach interlude he inserts into Knife Edge. He enlivened this music for an audience in the late twentieth century that likely would not have heard, let alone been “switched on” by it.

First, he was one of the early pioneers, and probably the best, at making classical music accessible and fun to a rock and rock mainstream audience. Although by the time I was exposed to ELP in my early adolescence I had already been playing classical piano for some time, hearing “Pictures at an Exhibition” really turned me on to want to seek out the original Mussorgsky. I found the piano works and gleefully stumbled my way through them. The same was true for his powerful adaptations of Copeland’s “Hoedown” and “Fanfare for the Common Man” and the use of Prokofiev in “Father Christmas.” As recently as a few days ago I was playing with the Bach interlude he inserts into Knife Edge. He enlivened this music for an audience in the late twentieth century that likely would not have heard, let alone been “switched on” by it.

Second, he was a virtuoso. The level of piano prowess and brilliantly crafted, technically challenging licks that he brought to all his keyboard compositions continues to astound. Later in his life he was cruelly plagued with hand injuries that robbed him of his gifts. What role this may or may not have played in his end, I can’t really say. I certainly prefer to remember him in his prime, with precise flying fingers effortlessly ripping off tasty riffs that I know by heart, and at the time could have only dreamed of executing, let alone concocting.

Lastly, he was a showman. As young keyboard player who wanted to come out from behind my gear and shine (read – impress the ladies) there weren’t many models to emulate until ol’ Keith came along. He could spin on his piano from on high, stab daggers into his Hammond and shoot sparks into the audience from his Moog ribbon controller. None of which felt silly at the time, but a genuine expression of playfulness with the music, and the audience. He knew how to be an instrumental star. One I will sorely miss.

Lastly, he was a showman. As young keyboard player who wanted to come out from behind my gear and shine (read – impress the ladies) there weren’t many models to emulate until ol’ Keith came along. He could spin on his piano from on high, stab daggers into his Hammond and shoot sparks into the audience from his Moog ribbon controller. None of which felt silly at the time, but a genuine expression of playfulness with the music, and the audience. He knew how to be an instrumental star. One I will sorely miss.

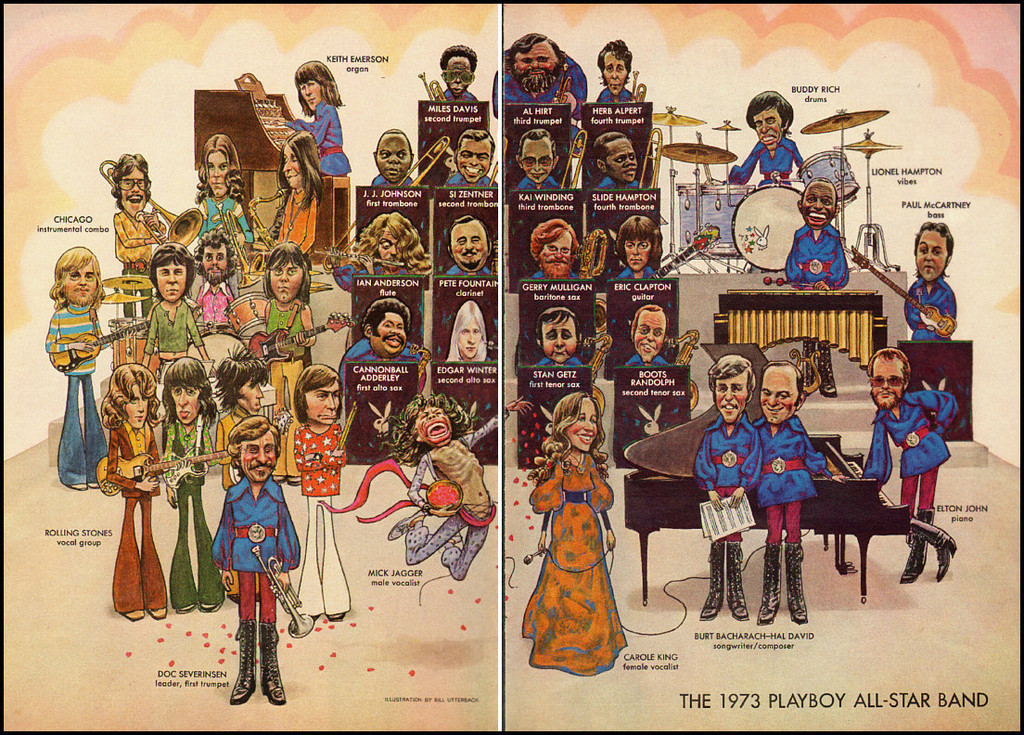

Although the images that will likely come up associated with the news of Keith’s passing will be him climbing on his Hammond, blades in hand, or in front of his monstrous Moog, analogue wires bursting at the seams – one image I remember from back in the day and wanted to share was his inclusion in the 1973 Playboy All-Star Band (when Playboy was Playboy), with quite an interesting cast of musical souls to boot.