Some advice for future attendees—arrive at least an hour before the first event to find parking nearby, and though you may have an advance ticket, it is imperative that you go to the event tent in the park to get a wristband to wear for the day. The website failed to mention that detail, at least not prominently, and the volunteers would not let anyone into events otherwise. I and many other attendees had to make late trips to the wristband line to remedy that situation. To Wordstock’s credit, I was able to work my way through the line, which was nearly a block long, in about ten minutes and still get a decent seat to my first event.

This was an interview with Tom Perotta, a novelist who has had several movies made of his books, including the HBO series The Leftovers. Its setting, First Congregational United Church of Christ on Park Avenue, was a bit ironic given the subject matter of Perotta’s most recent book, Mrs. Fletcher, which delves into internet pornography. Perotta presents his flawed characters, in this case outwardly respectable suburbanites obsessed with porn, with a lot of compassion and wit, and he delighted the audience with both of these qualities during the interview. The event was broadcast on OPB’s State of Wonder, which will be posted online sometime in the next few weeks. When Perotta signed my copy of Mrs. Fletcher afterward, I asked him if it was true, as I’d heard on NPR’s Fresh Air a few weeks ago, that he’d wanted the book’s title to be The MILF. He acknowledged that he had, but it made his publishers too nervous. “It was the F part they didn’t like,” he said. “People say WTF all the time, so go figure.”

The next event I attended was an interview with Ta Nehisi Coates at the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall next door. The place holds almost three thousand, and it needed all of its capacity to hold the multitudes that stood in a serpentine line in front of the building and down the side for about a block. I had read some of Coates’s articles in The Atlantic on occasion, but I had no idea he was such a rock star in the literary world. Unfortunately, his event fit the rock star stereotype in another sense by starting a half hour late. At one point, I thought people were going to start clapping and stomping like the Cleveland scene in Spinal Tap. Coates was charming when he finally appeared, but I left halfway through his interview to catch a nearby forum on Syria that I’d had my eye on. I stayed long enough to hear his suggestion that the scandal-free respectability of President Obama, far from mollifying his racist critics, likely provoked their anger all the more by threatening their cherished beliefs in racial superiority. It was as good an explanation as any, perhaps, for the hysteria surrounding Obama’s birth certificate.

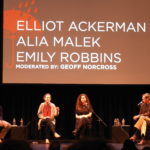

The Syria event, not as much in demand as Coates’s interview, was held in a correspondingly smaller theater space. The discussion included a moderator and three writers who had recently published books on Syria. Two were novels, including one by Elliot Ackerman, a former Marine who writes his stories from the perspective of his native protagonists. The other book was a memoir by Alia Malek, who lived with her extended family in Damascus and reported covertly on the regime during the first years of the civil war. The most touching part of the event was near the end, when the moderator asked Malek if she would consider returning to the country. She said that she would not, indicating that she was no longer welcome due to her reporting and that she would not return even if invited so as not to legitimize the Assad regime. Her emotions were visible on her face as she spoke, most likely because she was declaring a permanent exile from her family that remained in the country. It was a reminder of what writers can sacrifice on behalf of their work.

Afterward, I found a copy of Ackerman’s most recent book, Dark at the Crossing, which follows the journey of an Arab American traveling to Syria to fight in the civil war. When I approached Ackerman at a table of writers to sign the book, I told him that I liked his title. Hearing this, the writer sitting next to him asked if the title was his or if the publishers had chosen it for him. “It was mine,” he said, but the question and Perotta’s comments earlier in the day suggested that such was far from given when it came to publishing.

I tried attending one more event, another fiction conversation at the Congregational Church, but my attention span was shot by then. Seeking less challenging material to balance the day’s overload, I returned to my hotel to watch SEC college football and cable commentary on Roy Moore’s recently unearthed dalliances. At that moment, such material was just what the doctor ordered.