Colleges and cities have been wrestling as they consider monuments and buildings named on behalf of men who supported and profited from slavery or outwardly displayed racist tendencies in the earlier half of the 19th century and beyond. Tensions and protests have recently intensified across the country. On one side, people do not want to erase history; instead, they want confront and learn from it. What about whitewashing history in the name of “political correctness”? Others believe that removing monuments or changing names helps to come to terms with the past. Reveal or conceal?

At Harvard, in 2017, officials replaced a shield on a law school building that was the family crest of prosperous slave owners. The University of Minnesota decided last month to rename four buildings whose identities were linked to men who, e.g., kept residential housing segregated or secretly monitored the activities of Jewish students. The largest lake in Minneapolis, Lake Calhoun, is named after John Calhoun who died in 1850. Calhoun served as a U.S. representative and Vice President, was a senator from South Carolina, and defended slavery as a “positive good” that benefited both slaves and slave owners. In 2018, Minneapolis renamed the lake as Bde Maka Ska, a Dakota name that means White Earth Lake. Calhoun’s name will be removed from Yale’s campus.

Over the last several years Georgetown University, a Jesuit institution, has been grappling on how to confront its sale of 272 slaves to a Louisiana plantation owner in 1838. The movement started when a Georgetown undergraduate history major, Matthew Quallen, started publishing his research in the student newspaper, The Hoya, regarding Georgetown’s relationship to slavery. Historically, the Jesuits operated schools without charging tuition and instead relied on donations. This model became unsustainable, and even Rome got involved in the sale as a means to save the university.

Georgetown, a port city, had been heavily involved in the slave trade. Then the United States banned the importation of slaves in 1808, and it was not until the Abraham Lincoln era that slavery altogether became outlawed. In this span of approximately 60 years, upper-south states such as the Carolinas, Virginia, and Maryland began selling slaves to the southernmost states, most notably Louisiana, because the deep south heavily relied on cotton production, which was labor intensive. Remember, Eli Whitney invented the cotton gin in 1793 so more labor was greatly needed since post-picking production became significantly more efficient.

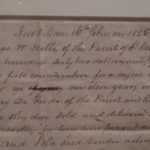

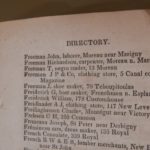

Under this backdrop, I was eager to visit the Illinois Holocaust Museum’s exhibit, “Purchased Lives: The American Slave Trade from 1808 to 1865.” Chief curator, Arielle Weininger, relied heavily on pieces from the Historic New Orleans Collection. For example, bills of sale noting special qualities of slaves are present. “Elizabeth, 20, fine washer and ironer, fair cook.” “Daniel (Tucker), 12, sprightly boy, [???] of foot in the dance.” The exhibit included a first edition of the book by Solomon Northrup, published in 1854, which was made into a movie called “12 Years a Slave.” Theophilis Freeman, the man who bought Northrup, is listed as a “negro trader” in a greater New Orleans address directory. An 1825 contract noted that a slave had been purchased for five hundred and sixty two dollars.

The exhibit did not contain a single reference to today’s debate on whether cities and post-secondary institutions should recognize slave traders or their wealthy benefactors who profited from slavery. Thus, this glaring omission sadly failed to connect the exhibit to an ongoing debate in current society.