In the artistic aftermath of “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band,” pop and rock critics were speculating about what would be the Next Big Thing in Rock. Some bands spun off into art and prog rock, others went back to the rootsy basics, and still others were helping along the evolution of folk-rock as it became country-rock. And in the midst of this rock ’n’ roll free-for-all, many other bands began supplementing their line-ups with horn sections that would not simply play punctuated riffs (as R&B bands traditionally had done with horns) but would instead incorporate roaring Big Band brass arrangements and jazz elements. Although it took a year or so for horn-driven rock to catch on with the public, once Blood, Sweat & Tears fired co-founder Al Kooper and replaced him with barrel-chested blues shouter David Clayton-Thomas, they recorded one of the biggest-selling albums of 1969, won a boatload of Grammy Awards, and landed the first big commercial blow for what was initially called Jazz Rock (and by the late ‘70s referred to as Fusion).

After that, it would be another 2-3 years before Chicago would fully emerge from the brass-pack and go on to eventually become America’s favorite band with horns. But in the meantime, it was BS&T’s success that created the relatively short-but-successful template for horn bands. And they all wanted to be the next Blood, Sweat, and Tears.

CHASE

Despite the myriad of imitators that followed, only two big hit horn-driven singles attained anything that neared the chart-topping success of Blood, Sweat & Tears – “Vehicle” by the Ides of March and “Get It On” by Chase. And though more sophisticated ears could hear the differences, the two bands had followed the BS&T template so closely that much of the public mistook both bands for Blood, Sweat &Tears.

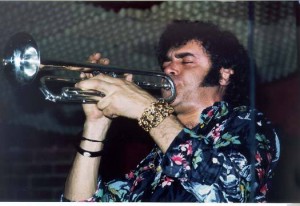

Of the two, though, only Chase’s jazz and talent cred was nearly the equal of Blood, Sweat & Tears, with leader Bill Chase previously having established himself as the lead trumpet player in Woody Herman’s Thundering Herd, a jazz band that featured a fearsome, screeching brass section that some claimed could break glass because of the high frequencies Bill Chase reached on his trumpet.

But Bill was hungry for broader public success, and when he noticed the then-massive popularity of BS&T, he jumped ship from Woody Herman’s jazz orchestra. Gathering several young, hot, and hungry trumpet players from some of the Midwest’s leading university jazz programs and teaming them with a bottom-heavy blues-rock rhythm section, Bill named the new band after himself and fronted them with a David Clayton-Thomas quasi-soundalike.

Success was immediate, and Chase’s debut single roared out the gate, hitting the AM radio charts with the horns-a-blasting “Get It On,” which was one of the hottest singles of 1971, characterized by its screaming trumpet cascades, aggressive bass and drums, and lustfully urgent lead vocals. It flew up the charts and became the soundtrack for thousands of teenagers making out to its sounds on the car radio.

Unfortunately, nothing else Chase did matched the intensity or catchiness of “Get It On.” The band’s first album was full of good-though-somewhat-similarly arranged songs and an ambitious side-long suite, but none of the work approached the sheer ferocity of “Get It On.” The band recorded two more albums and kept replacing lead singers – one of whom, incidentally, was Jim Peterik, the erstwhile leader/singer of the afore-mentioned Ides of March and composer of “Vehicle,” who was later to write and sing “Eye of the Tiger” for Survivor – but, frankly, Chase lacked the depth or breadth of the band whose template they’d adopted. BS&T had built its reputation with inventive bluesy arrangements of classics like Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child,” horn-concentrated versions of song by well-respected pop and soul writers like Carol King (“So Much Love,” “Hi-De-Ho”) and Berry Gordy’s Motown writers (“You’ve Made Me So Very Happy”), and jazzy takes on songs written by an emerging generation of young, exciting songwriters like Randy Newman, Harry Nilsson, Laura Nyro, and Steve Winwood. Additionally, David Clayton-Thomas himself wrote highly accessible rock tunes of his own (“Spinnin’ Wheel,” “Go Down Gamblin’”), and his expressive voice lent itself to a broad interpretative range of material.

Although the Chase horn section was clearly the equal of BS&T, by contrast Chase’s song repertoire and arranging and vocal chops were qualitatively lesser. Despite that, Chase’s joy in playing, and the thrill the band felt in creating a brassy sonic avalanche was abundantly clear and was exciting. Though they tried to reinvent themselves as a more unapologetic jazz-fusion band on their third album, they did not have time to complete the vision. Shortly thereafter, Bill Chase and several members of the band were killed in a plane crash.

Nonetheless, despite the band’s limited repertoire and Chase’s undeserved one-hit wonder status, “Get It On” remains a sonically exciting recording – a highlight of the early Seventies brass-oriented sound — a screaming, blasting equal to the very best from those heady, early days of Horn Rock. Let it blast your ears anew.