There is a long and somewhat intellectual debate as to who (which country) gets to lay claim the title of creator of the cocktail (hint: its America). The British play a large part in the effort, but from the beginning it was considered an American creation and recent research seems to place it squarely in the front yard of the upstarts across the pond from England – likely somewhere within a regional triangle bounded by Boston, Albany, and New York City. In 1803, the Americans used the term as we know and accept it today in print for the first time in the Farmer’s Cabinet newspaper, and then three years later The Balance and Columbian Repository of Hudson, New York, gives the cocktail the strict formula that we still use – “a stimulating liquor composed of any kind of sugar, water and bitters, vulgarly called a bittered sling” – with a sling being a pre-revolutionary alcoholic drink. Some still disagree (Hint: the English), but the matter seems to be settled unless a yet-unknown text comes to surface. So, onto to where the name comes from.

There are several competing stories about where the term “cocktail” comes from – or I should say there were a series of competing stories. Recent etymologists have settled on a very interesting origin story. As early as 1616 we see references to “feaguing” a horse prior to a sale. Let’s say you had an older horse to sell, and lets also say he (or she) looked ‘rode hard and put away wet’. You might grab some raw ginger root and peel the skin off, then slide it right into the horse’s . . . fundament. This peppery suppository would burn and make the horse raise its head and flick its tail as it pranced about. This became known as ‘cock-tailing’ the horse, because of the cocked tail. The buyer might think he was buying an energetic yearling, but instead once the burning ended (with thankfully no injury to the horse) he would find that he purchased a run-down nag. The reason we see it in print, is the practice was illegal, and could negate the contract of the sale.

The unscrupulous seller grabbed ginger because it had been used as an herbal wake-me-up for centuries. Ginger became one of the fundamental elements of the tonics and elixirs that people used to cure all form of medical issues – all the way back to the ancient Egyptians. These tinctures made from infused roots and herbs came to be known as ‘bitters’ in the late 1600s. We even see it added to drinks in bars as a morning pick-me-up in England in the 1700s. The term ‘ginned-up’ also comes from this practice – “to create, by artificial or dubious means”. But the Americans, as they do, took something someone else had created, and then made it better and globalized it (think frankfurter/hot dog. When was the last time you went to a baseball game and ordered a frankfurter)?

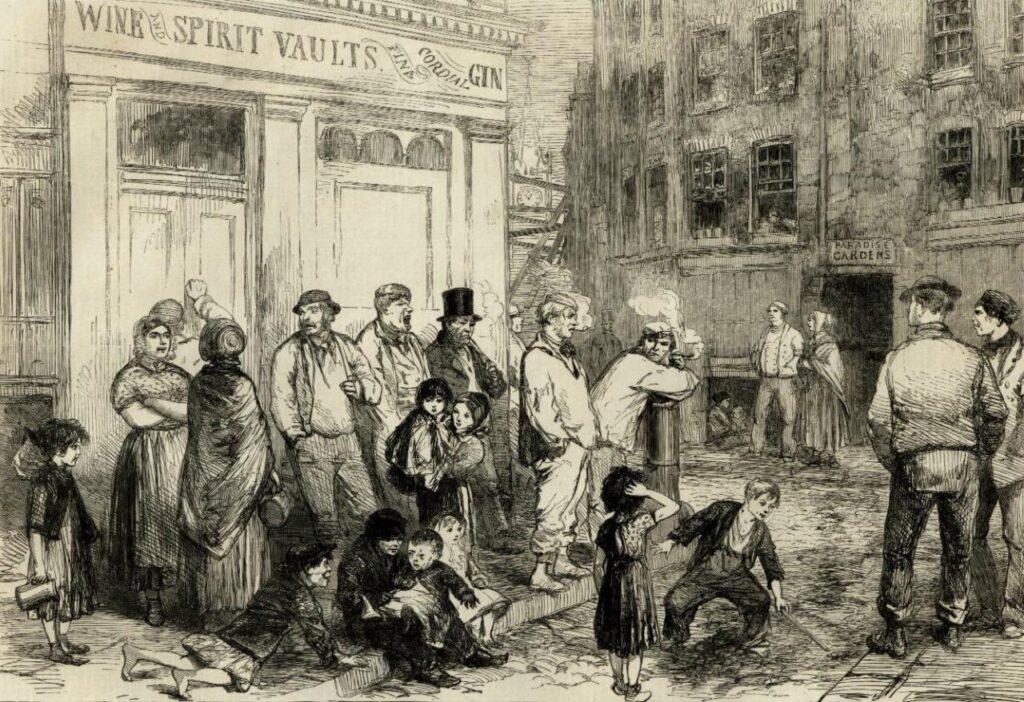

Now zip forward to post-Colonial America. No one, and I really do mean no one, drank as much as American’s did after this country was formed. We were drinking three times as much as we do now in the first several decades of the 1800s. We drank hard cider with breakfast, ale for lunch & afternoon break at work (during ‘Grog Time’), then went home and drank more ale with dinner, and madeira (fortified wine) until bedtime. Some of this was due to the scarcity of clean drinking water – but mostly just because Americans liked to drink. And all this drinking caused a lot of hangovers. A lot.

Enter the cocktail. What Americans really needed was some daily ’hair of the dog’. A ‘corpse reviver’. An ‘antifogmatic’. They were going to drink anyway, so why not add medicine (bitters) and sugar to it. Just to clear the head and give a guy some artificial get-up-and-go in the morning. Spirits, water, sugar, bitters. The morning medicinal cocktail was born. The cocktail allowed someone to ‘settle the nerves’ so they could get on with their drinking for the rest of the day. After all, its difficult to create a new country with a hangover.

Next: The Flip

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail

- Bill Stott