Pilgrims landing on Plymouth Rock

“We could not now take time for further search or consideration, our victuals being much spent, especially our beere.” – from the diary of William Bradford

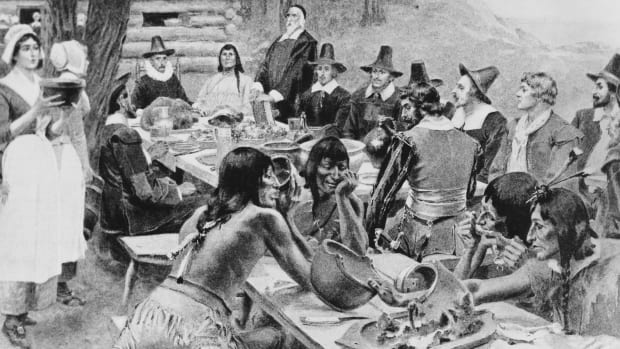

The story of the Pilgrims and the first Thanksgiving is an interesting one. Black and white clad Puritans sitting down with half naked natives and sharing a meal to celebrate the thankfulness of the harvest. It is a tale fabricated sometime in the early 1800s – Pilgrims who escaped religious persecution, struggling through their first winter in a strange land, accepting the aid of a local Indian tribe to help keep them alive, and teach them how to survive in this strange land. But most of what we have been told is a fabrication of the truth. Righteous Christian men and women facing the odds to bring their brand of Christianity and purity to the New World and establishing a foothold here. Like all stories, it is rooted in the truth, but this story is greatly sanitized. Which is sad, because the real story is far more interesting – and in my opinion, far more American. The Mayflower was destined for the English colony of Virginia, which extended roughly north to the Hudson River. But we celebrate the 1620 landing at Plymouth Rock, in what is now Massachusetts, 220 miles north. One reason was weather. But another reason had to do with beer.

The Mayflower

The Mayflower was stocked with 42 tons of beer and 10,000 gallons of wine, but the two-month Atlantic crossing took them far off course, and longer than they were expecting. Their sister ship, the Spedwell, kept leaking so all the passengers and cargo were transferred to the Mayflower and the cramped ship left Plymouth, England alone a month late on September 6, 1620. For as long as men have been sailing, there has been no way to bring enough water to stay alive on long voyages, so the water was fermented into beer and wine. Water would become brackish and full of bacteria, but even the lightly alcoholic ‘ship’s beer’ would stay fresh and drinkable for months while stored aboard the boats. One of the major benefits of alcohol is that it could be stored in simple wooden barrels for long periods of time. But the additional passengers and weather delays put their rations in short supply, and the hired crew still needed enough beer to travel back to England. All abord were given a gallon of ale a day, as the grain was thought to give nourishment and hydration needed for the voyage. When they finally sighted land, Captain Christopher Jones kicked all the passengers off the boat. Puritan William Bradford, who later became the Governor of the Plymouth Plantation, complained in his diary that he and other passengers “were hastened ashore and made to drink water, that the seamen might have the more beere.”

This quote. perhaps more than any other in American history, has been parsed, debated, argued, embraced, and discounted. The crew and the Pilgrims (Less than half of the passengers on the Mayflower were Pilgrims, or ‘Saints’ as they referred to themselves. The rest were passengers looking to make their way and their fortune in the New World) did not get along – so it is natural they would want to be rid of the self-righteous group as soon as possible. The crew still held out hope to return to England before winter, but after a few attempts to make their way south, they resigned themselves to staying until spring. The Atlantic Ocean at this time of year is a fickle beast, and the short trip south was highly dangerous in the late fall. The captain eventually did allow the new refugees back onto the ship but urged them to find their own accommodations.

The first savage winter

The Pilgrims were very suspicious of the New World’s water and did not like the taste. Other than a ration of beer to celebrate Christmas on board the ship, they had to make do on their own throughout that first winter, during which half the new settlers and crew died (45 of the original 102 colonists perished). It is likely that they carried the simple supplies to make beer once on land, but that would not have lasted long. There is much debate as to how much the “victuals being much spent especially our beere” played into their decision to stay, but Bradford talks about provisions a number of times in his diary, so it is difficult to say it had nothing to do with it. The Virginia Colony was a thriving English corporate settlement, intent of reaping the spoils of the new land and sending the wealth back to the King. They would have fared much better that first winter in the English Colony, but then they would have ended up forgotten along with the thousands of others arriving in the New World to make the King rich. This area was still wilderness, and while white English men had been visiting the area for decades, they were all alone. The fact that they ended up outside the Virginia Colony meant that they were their own settlement – outside the laws and protection of the Crown. This required an agreement in writing, binding the “saints and strangers” as William Bradford called the motley group of Puritans and other settlers. The 41 men signed the loose governmental agreement, which came to be known as the Mayflower Compact – and it is the foundation for the Declaration of Independence that followed 150 years later.

The signing of the Mayflower Compact

They sheltered off and on the ship all through the northern winter, which they were ill prepared for. The Mayflower finally left for the return voyage on April 5, 1621, and the settlers discovered an uninhabited Indian village to live in with fields adjacent, ironically abandoned thanks to a regional Smallpox outbreak several years before brought by a previous wave of white settlers. And more ironically, the friendly natives we see in the classic paintings, the Wampanoag Indians, were actually strategic defense partners, protecting each other from more aggressive and lethal tribes. The Indians taught the Pilgrims how to hunt and farm, and the Pilgrims had muskets. The righteous Christian Puritans turned out to be good partners, as they were brutal fighters, not adverse to ambushing and killing unarmed rivals.

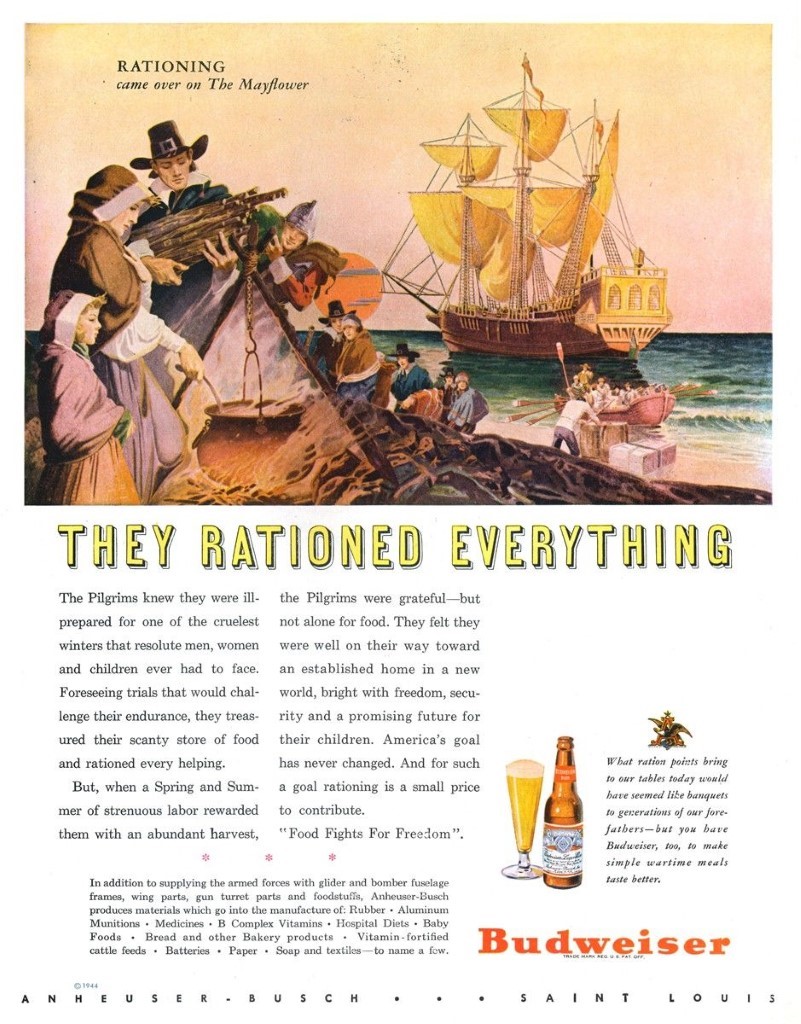

But back to the beer. There is a mid-1800 Temperance aspect to why alcohol is never talked about in the storybook version of Pilgrim story. We can’t have the religious torchbearers of America soiled with the stench of beer, so it is discounted in history. To counter this, during the first decade of the next century, Anheuser-Busch began producing ads prior to Prohibition to build up the notion that beer was as American as apple pie (and the Pilgrims). This effort returned again after Prohibition was repealed to get people drinking beer again and became an annual Thanksgiving campaign well in to the 1940s. But the truth is somewhere in the middle, and it does not include the kind of beer you are thinking about.

Budweiser ad during WWII, on the topic of Rationing

As mentioned earlier, even low alcohol content beer was considered safe to drink compared to water. But there was no malt in the New World. The Pilgrims likely did what everyone else did at the time – they improvised. The Dutch had a functioning brewery as early as 1621, and the Roanoke Colony experimented with making beer from corn as early as 1584 (before they disappeared). There are accounts of using corn stocks, pea hulls, and even pumpkin to make beer – information that would have been widely known at the time. These were not included for flavor, but as fermentable sugars in place of the malt. The result would have been likely disgusting to today’s craft brewers and drinkers – but this was not something to drink as you were stealing glances at the young gal with the Scarlet Letter on her dress. This was simply to help keep you alive. It is said that the local natives taught the Pilgrims how to make a fermented beverage out of corn, common to many native cultures in America, Central America, and South America. It had a very low alcohol content – and was probably fermented for the same reason fermentation sprang up in every continent independently of each other over the long arc of history. It was safe to drink.

So maybe there was beer at the first Thanksgiving after all.

Happy Thanksgiving to all – and please stay safe.

Cheers!

- Bill Stott

AotCB-017

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail