People ask me all the time. What do you do with bitters? Or – what are bitters for? The short answer is they are to cocktails what spices are to food. Chef and author Samin Nosrat says of salt, “Salt’s relationship to flavor is multidimensional: It has its own particular taste, and it both balances and enhances the flavor of other ingredients”. The same is true of bitters. You don’t salt your food to make it saltier – you salt it because it brings out underlying flavors. In the same way, adding bitters to a cocktail – even a drop or two – changes the flavor profile of the drink and pulls botanicals or cask undertones out. It can convince you that the drink is creamier or richer. If you are going to make a cocktail – bitters are essential. A cocktail, compared to a julep, a collins, or a flip, is a drink with a minimum of four must-have components: spirit, water (ice), sugar, and bitters. This is a formula that has been accepted since printed in the Balance & Columbian Repository of Hudson, New York, in 1806.

Bitters have been around a long, long time – far longer than the term bitters. Spices, roots, and bark have been added to water and wine since the ancient Egyptians, who infused medicinal herbs in clay jars of wine. Their qualities to aid in digestion and to calm stomach ailments stretches across the continents to multiple cultures (you can probably find bitters sold in health food stores as digestive aids even today). Bitters were first patented in 1712 by doctors prescribing them for stomach ailments and were often taken with alcohol. That first cocktail listed in 1806 – it was to be taken in the morning to recover from too much drink the night before. The 1806 version of a hangover cure.

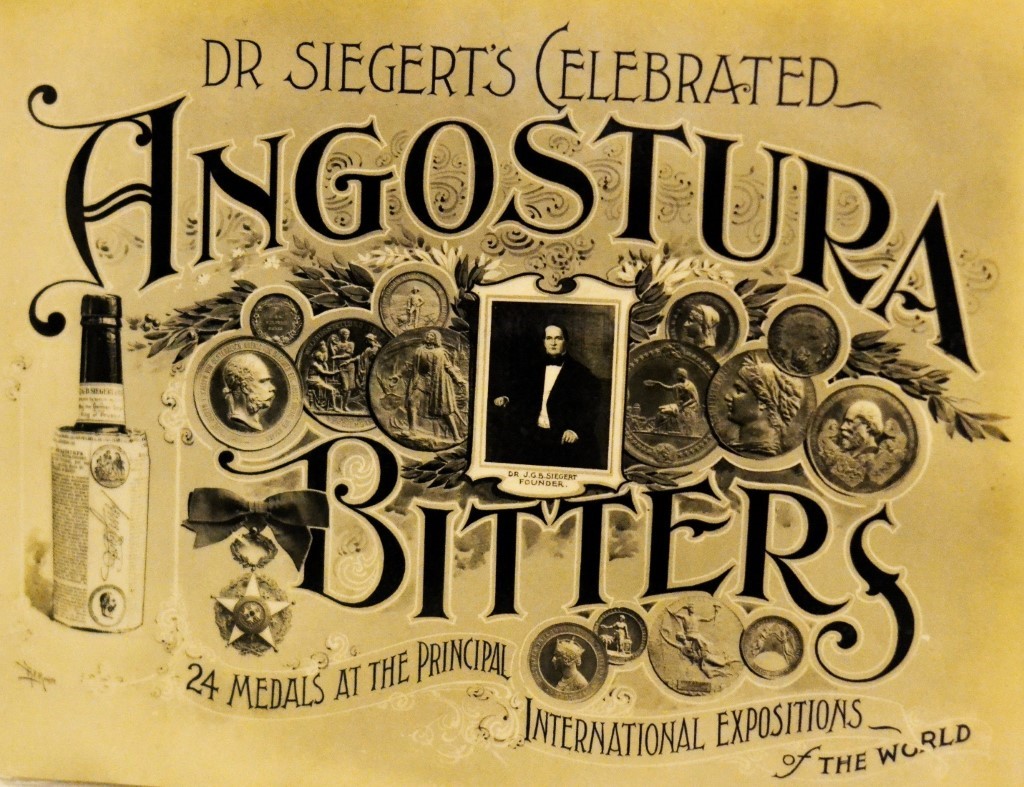

In 1690, London newspapers included ads for a new product – the “Elixir Magnum Stomachicum”. The tincture of roots, bark, peels, etc. was sold from an apothecary run by Richard Stoughton, its creator. He recommended adding them to brandy or wine as a hangover cure. Then in 1824, a doctor in Venezuela, Jonann Siegert, created a mixture of local herbs and roots, and mixed it up with a high-proof neutral spirit to create a stimulant to help soldiers with malaria and to keep them on their feet. Siegert was the surgeon general of Simon Bolivar’s army in the town of Angostura, and he named the concoction Dr. Siegert’s Aromatic Bitters, later renamed Angostura Bitters. In 1862 his son brought the bitters to England, mixed them with gin and introduced the drink Pink Gin to the Queen – and the world. The secret Angostura recipe remains the same, even though it is now produced in Trinidad, and only a handful of people know the actual components.

By the Civil War, bitters were so ingrained into the American psyche, that the Union Army supplied soldiers with “Hostetter’s Celebrated Stomach Bitters” to help gird them against the “fatal maladies of the Southern swamps, and the poisonous tendency of the impure rivers and bayous.” These bitters were referred to as the ‘Soldier’s Safeguard’, and likely had little beneficial effect other than a little liquid courage from the 94-proof tincture. But the 20th century was not kind to bitters. Prohibition cracked down on their medicinal claims, and they had a good decade or two after, but never really recovered until the 1990’s when the cocktail renaissance bloomed back to life. As late as 2000, the only bitters you were likely to find in a bar – outside New Orleans – was the old standby, Angostura (New Orleans always had a soft spot for Peychaud’s Bitters, essential to the Sazerac). Now, we seem to be awash in bitters. If you can think of a flavor profile, it probably already exists in a bitters. So, what do we do with them? Below are the most popular bitters on the market – and what their best use is.

Angostura Bitters

If bitters are like seasonings, then Angostura, or Ango, is the salt of the bitter world. This mixture has remained unchanged for almost 200 years. The aromatic bitters have a Caribbean spice profile, with hints of clove and cinnamon, adds depth and complexity, and pulls the different ingredients of the cocktail together (and food, according to the company). It is mostly associated with the Old Fashioned, the Manhattan, Pink Gin (really delightful), and Tiki drinks.

Fun fact, the oversized label was an ordering error by the company. One of Dr. Siegert’s sons took responsibility of ordering the bottles for a competition, while the other son ordered the labels – neither communicating with the other. In one of marketing’s greatest examples of making lemonade, the oversized label became so recognizable, that the error was never corrected.

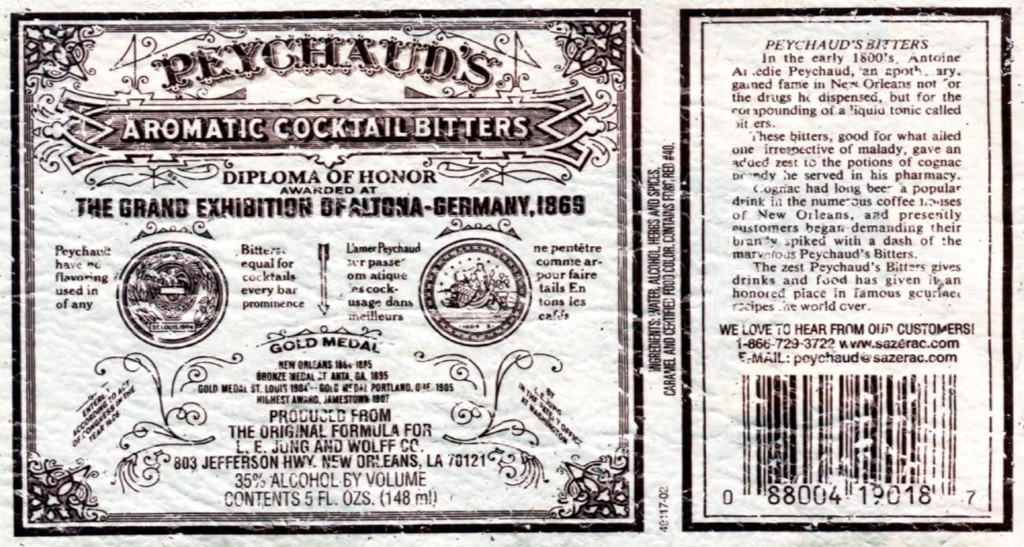

Peychaud’s Bitters

These bitters were created around 1830 by Antoine Amédée Peychaud, a Creole apothecary from the French colony of Saint-Domingue (now Haiti) who settled in New Orleans in 1795. The Creole bitters are similar to Angostura, but the gentian root mixture has hints of anise and a background of mint. It is linked to that New Orleans legend, the Sazerac and its relative the Vieux Carre. Peychaud’s is often used as an aromatic ‘cap’ on drinks, as the bright cherry-red color is striking.

Orange Bitters

While orange bitters are relatively new to the scene again, they have a long history and have become essential to the modern bar. By the late 1800s, a host of cocktails used orange bitters, and iconic barman Jerry Thomas references them in his 1862 book ‘How to Mix Drinks’. But they became lost to history. While both Angostura and Peychaud’s are proprietary and secret recipes, there are a slew of companies currently making orange bitters, with many bars and mixologists mixing different orange bitters together to make a unique flavor enhancer. Orange bitters are typically made from the zest of bitter orange peels, and mixed with gentian root, cinnamon, cardamom, fennel, cloves, and/or ginger. Orange bitters are closely associated with the Bijou cocktail, the Bronx cocktail, and the Fifty-Fifty martini – all popular cocktails before and in the decades right after Prohibition (both the Bijou and the Fifty-Fifty are perhaps two of the greatest cocktails ever created). But by 1960, orange bitters were all but extinct.

And All the Rest

If you are only going to have three different bitters – those are your three. Think of them metaphorically – not literally – as your salt, pepper, and sugar. Beyond those three, the choices tend to lend themselves to a smaller and smaller collection of cocktails. Death & Co., the iconic mixology bar in New York City, classifies bitters as either Lifting Bitters or Binding Bitters. Lifting bitters heighten and brighten flavors within the drink. They are usually based on one ot two main ingredients or flavor profiles, and include Celery Bitters, Vanilla Bitters, Tiki Bitters, Grapefruit Bitters, Walnut Bitters, and Orange Bitters. The Bittermens Hopped Grapefruit Bitters would be my fourth pick for your bar.

Binding Bitters, on the other hand, connect the various flavors within the drink and tie them together. “Like a zipper”. These are typically your aromatics: Angostura, Peychaud’s, Jerry Thomas Bitters, Xocolatl Mole Bitters, and again – Orange Bitters. The Bittermens Xocolatl Mole bitters would be a great addition as well. The chocolate/cinnamon/spice bitters, based on the traditional Mexican mole sauce, was created to pair with tequila, but it works well with other dark and aged spirits: dark rum, bourbon, or rye. Give it a shot in your Manhattan.

The best part of bitters – they are fun to play with. Start with soda or tonic water and add a few dashes – but be aware that a dash is not a drop. Give the bottle one good shake, as a dash equates to about 6 drops from a dropper. Get to know the flavor profiles, then start to add them to your cocktails. I was recently introduced to walnut bitters in an Old Fashioned – and once again surprised how the few milliliters of liquid can change a drink completely.

Cheers!

- Bill Stott

AotCB-019

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail