I burst into tears this morning, reading that another bit of my childhood was gone. It surprised me at first, my brief waterfall, but then I realized that I couldn’t be the only one.

It has been said that you could tell that The Hammer (never to be confused with another iconic slugger, Hank “The Hebrew Hammer” Greenberg) was at the plate during batting practice from the sound. Powerful man, powerful wrists making an unmistakable sound. The Hammer wasn’t really a home run hitter, ironically; he was a line-drive hitter. Home runs were accidents. You could identify one of the finest hitters in history during BP by the sound of nails being hammered into the old outfield walls.

“Bam!” “Bam! “Bam!”

He carried himself with a braggadocio-free dignity, from day one. He came from nothing, and became one of the greatest sportsmen in American history. He endured racism’s slights and barbs and stings and stupidity, only to graduate to death threats as he approached immortality.

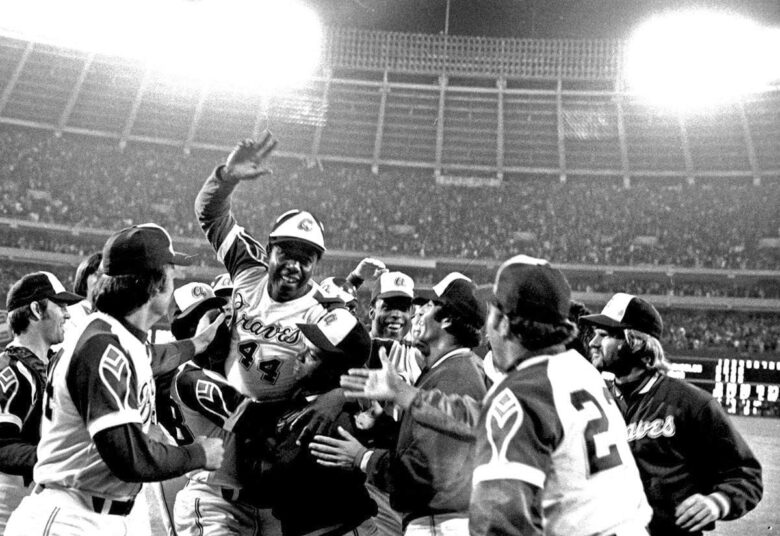

The Hammer broke the record when I was six years old, and retired not long after that – yet, he seemed like he played throughout the 1970s. His name was everywhere; his feat and his stature, omnipresent. The Hammer’s legend became the stuff of oral history long before he laid down the bat, though; like Paul Bunyan – or, perhaps more appropriately, John Henry – the legend has grown with reverence over time. The Hammer was larger than life, yet a humble figure. A deity who, like DiMaggio, had achieved something no one could ever surpass. A deity who, unlike DiMaggio, made his mark with police protection.

To allow a doper, a juicer, a cheat to even think of officially recording a higher number than 755 is a stain upon baseball…. but according any lesser man than The Hammer – or Josh Gibson – that sort of honor is an even darker, more shameful blot. The record belongs to great men, before athletic abilities are considered.

Though well aware of the color of his skin, I did not think of The Hammer as a black man. Nor did I think of Kirby Puckett, Ozzie Smith or Andre Dawson as black men. They were just men, just athletes. My generation was arguably the first not to think in terms of “black ballplayers,” and The Hammer had a great deal to do with that. He gracefully transcended racial distinctions as he eclipsed the game itself.

I met The Hammer once, as a young man. I wish I had children, so I could tell them the story. It was a fleeting audience with a god.

Hammerin’ Hank Aaron, one of this country’s greatest men, has left the ballpark.