The Tequila Shot

Every college student and football tailgater knows that chant. You lick the skin on the back of your hand between the thumb and pointer finger and shake salt on, then grab a lime wedge with the same hand. With your free hand, you grab a shot of tequila and in time with the chant of those around you, you quickly lick the salt off, toss the tequila back, and bite into the lime. Everyone knows the chant – but in all the years I have heard it (and all the shots I have taken) it never occurred to me that there was a story behind it. But first, a little history on the agave spirits.

The first thing you need to know about the difference between mezcal and tequila, and this is possibly the only thing you need to know, is that all Tequila is Mezcal – but not all Mezcal is Tequila. Just as every bourbon is a whiskey, but not all whiskeys are bourbon. Mezcal can be made from any combination of the 50 species of agave plants native to Mexico and made in one of nine Mexican states: Durango, Guerrero, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Oaxaca, Puebla, San Luis Potosí, Tamaulipas, and Zacatecas. Tequila, on the other hand, can only be made from one agave – the Blue Agave. To be classified as tequila, at least 51% of the sugars must come from the Blue Agave, while the rest can be made of other sources – typically cane sugar. That is why tequila made from 100% blue agave is considered a premium spirit.

But terroir matters. The French term references the environmental factors that can affect the taste of the sugar, agave nectar, and ultimately the spirit. Ignoring differences between the three main types of tequila – blanco, reposado, and añejo – this is why the spirit is so consistent. And why tequila is preferred over mezcal in America, where we tend to not like to be too challenged when it comes to alcohol. The best selling beer? Budweiser. The single plant and smaller geography results in a consistent product.

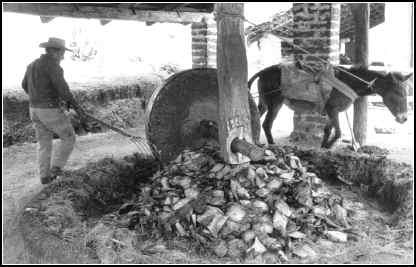

Mezcal, on the other hand, brings much more variety to the table – both in species and terroir. Tequila is a relatively clean, neutral spirit, while the flavor profiles for mezcal include words like roasted meat, rubber, gasoline, lychee, rosewater, and bubble gum. The different soils and even weather play a role in the final taste of mezcal. The preparation is different as well. In both cases, the long spiny fiber-rich leaves are cut off by the jimador (harvester), leaving the plants pina, or inner core – sometimes referred to as the pineapple. That’s where the similarities stop. For tequila, the pina are placed in a stainless steel autoclave (older distilleries still use brick ovens) to cook the pina. It is then shredded, fermented, and distilled in copper pots. For mezcal, the pinas are dropped into a volcanic rock lined underground pit-oven. A fire is lit and then the oven is buried. Once done, the pinas are shredded, fermented, and distilled in clay pots. This is what gives mezcal its signature smokiness, and the taste of caramelized sugar.

It’s an interesting fact that the fermentation of natural sugars – grain, fruit, rice, tuber, cane, agave – occurred independently in virtually every civilization across the globe. Many believe the planting of grains to make beer is the reason nomads began settling in one area, creating the first cities. The agave plant has been used by the indigenous people of Central America for at least 9,000 years, and the mildly alcoholic pulque (a white, foamy alcoholic beverage, made from fermented sap from the agave plant) is listed in the earliest records, By the time the Spanish arrived in the early part of the 1500s, it was already considered an ancient drink.

Just as the pilgrims began almost immediately sourcing materials in the New World to make beer and wine, the conquistadors quickly turned to the agave to make a replacement for their limited supply of brandy. Water was dangerous – especially in a new region, and a safe source of potable liquids would help them survive. The fact that it would get them drunk was a bonus. By 1520, distillation of the fermented sap began. In 1600, Don Pedro Sanches de Tagle, the ‘father of tequila,’ set up the first tequila factory, producing ‘mezcal wine’ for nearby Guadalajara. The first licensed manufacturer of mezcal was Jose Antonio Cuervo (yes, that Jose Cuervo), who got the rights to cultivate a parcel land from the King of Spain in 1758. The indigenous Nahuatl Indians called the agave plant metl or mexcametl – and the bastardized form of the word became mezcal.

Sometime within the first two decades of the 1800s, Jose Castaneda founded La Antigua Cruz tequils, which was purchased by Don Cenobio Sauza in 1873, changing the name to La Preservancia in 1888. Cenobio is credited with determining that the blue agave was the best maguey (the term for the large collection of agave plants of Mexico) for making tequila, and others soon followed. The distilled product was referred to as mezcal wine, mezcal brandy, agave wine, mezcal tequila, and finally just tequila, named after the town of Tequila, in Jalisco state, Mexico.

In 1785, Spain’s King Charles III prohibited the production of mezcal tequila to promote the sale of Spanish produced wines in Mexico. But rather than stopping production it went underground. Literally. The cooking of the pina began taking place in buried ovens. The ban lasted until 1792, but the underground pit-ovens remained and became an integral part of the production of mezcal.

Thanks in part to the new network of railroads across North America, ‘mezcal brandy’ quickly entered and spread across the Unites States – even winning a prize at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893. And it is approximately this time when the mezcal produced in Jalisco shortened the name of their product to simply tequila.

Mezcal and tequila were fringe alcohols until Prohibition hit, and it began creeping across the border in greater and greater amounts. Tequila’s reputation grew in part thanks to the proximity to open bars right across the border. Over 100 bars in Tijuana alone catered to thirsty Americans. Once Prohibition ended and people could once again purchase the alcohol of their choice, the agave spirits faded back into Mexico.

So now we come full circle in this little story. In 1941 the Japanese attack Pearl Harbor, thrusting the US into World War II. In 1942 the US Government banned the production of domestic gin and whiskey and required the distilleries to retool to make industrial grade alcohol for the war effort. A nationwide shortage of alcohol ensued, and tequila once again headed back north to replace gin. Most was low quality with an obnoxious odor and taste, and author Davis Embury suggested drinking a dilute acid first to counteract the foul smell and taste – using salt and citrus juice. The ‘Mexican Itch’ develops – licking salt off your palm then eating a lime – then finally downing the shot of tequila. No one knows why or when the lime and tequila switched order, but tequila improved, and the ritual was no longer needed to hide the taste and smell. Its now just a party trick.

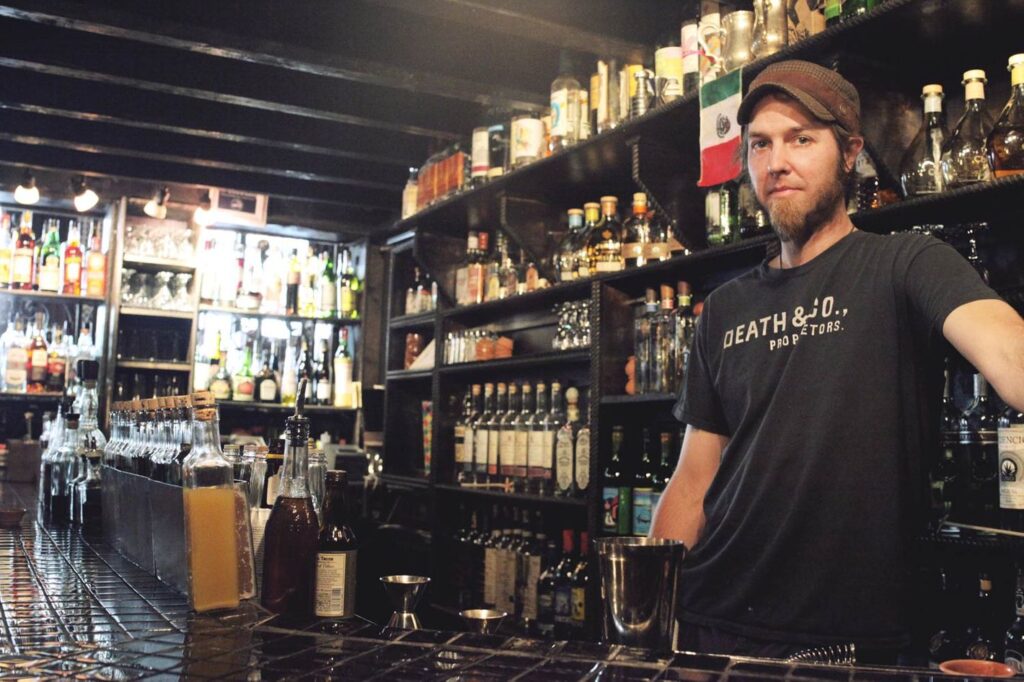

And mezcal – it took until the cocktail renaissance in the first part of the century to find a foothold in the US. Many credit Phil Ward, the legendary mixologist in New York City, with almost singlehandedly bringing mezcal into the mainstream. After cutting his teeth at Death & Co., the Pegu Club, and the Flatiron Lounge, Ward opened his first bar, Mayahuel, in 2009 in the East Village (which sadly closed in 2017) specializing in mezcal. It is now common to substitute blanco mezcal for gin and light rum, and aged mezcal for whiskey and cognac – but before Ward, that sentence would have seemed ridiculous. With one drink – the Oaxaca Old Fashioned (an amazing cocktail) – Ward made mezcal a world-wide sensation.

And of course – what’s up with the worm? No one really knows where the worm came from, but all agree it is only present in mezcal. A moth larva, not a worm, the stowaway began appearing in cheap bottles of mezcal in the 1950s. The story goes that a distiller added the larva to each bottle to add a special something extra to improve the flavor of the spirit. The story also goes that it was a marketing ploy from the beginning to get noticed, and it caught on. Soon everyone began copying it. There is also a rumor that if you eat the worm, you will hallucinate. Not true, At least for the worm. If you drink a bottle of mezcal to get to the worm, well that might make you see things.

So, if you see a bottle of mezcal with a moth larva drifting around in the bottom of the bottle, avoid it. Not because of the worm – but because that’s a sure sign it is a cheap mezcal.

Cheers!

Bill

AotCB-028

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail

MORE TEQUILA: Architecture of the Cocktail: New Spirit Monday, by Bill Stott