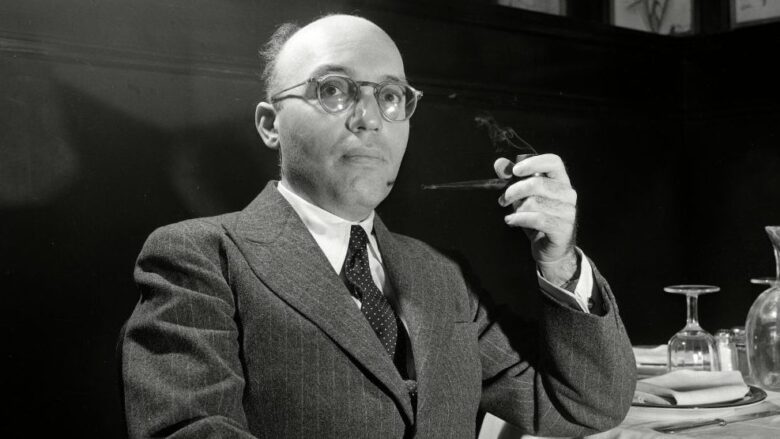

Kurt Weill at Sardi’s, 1943. Photo by Dan Grossi/Associated Press

I recently embarked with soprano Juliana Brandon on a major project to develop and (when the pandemic lockdown ends) perform our own arrangements of the music of Kurt Weill (1900-1950). There’s a bit more to it than that, and you can read all about it at http://weillproject.com/ or https://www.facebook.com/groups/299892691477483. Weill left the world of German classical music to focus on the cabaret and theater music that was the main popular music of the era. You probably at least know “Moritat (Mack the Knife)” with lyrics by Bertolt Brecht, now a jazz standard; and “Alabama Song (Whiskey Bar)” with lyrics by Elisabeth Hauptmann, covered by both The Doors and David Bowie. Both of these were written in the 1920s. Or perhaps you know “September Song” with lyrics by Maxwell Anderson, performed by everyone from Frank Sinatra to Lou Reed, written in the 1940s after Weill escaped Nazi Germany and became an American.

I’ve known much of Weill’s music all my life, but looking toward performing it I’ve been thinking more and more about where he fits in the history of Twentieth Century popular music. I was born in the Fifties, so my musical comparisons tend to be most from the rock era. The only figure I can think of in the second half of the Twentieth Century whose career resembles Kurt Weill’s is John Cale. Cale studied under Aaron Copland, was connected to the Fluxus artists (the best known of whom now is probably Yoko Ono) and in the same period where first played casually with Lou Reed, Cale was performing with La Monte Young, classically-trained experimentalist and pioneer of minimalism and drone sounds in classical music. Future Velvet Sterling Morrison sometimes played with them as well. You can find recordings under the name The Theatre of Eternal Music. They are worth looking up. Check out “The Over Day” (online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=guMI0SMKGbg&t=1055s) if you want to understand how much of the Velvet’s sound was Cale. “Just add rock.”

Cale carried that drone and other classical ideas into the Velvet Underground and opened up a completely new direction in the possibilities of rock music, way more interesting than the obvious surface classical borrowings in ELP or Yes. Listen to “Heroin,” first released on The Velvet Underground and Nico, where, once Cale comes in, he maintains a single high drone note on the electric viola for almost five minutes, double-stopping to get in other notes as well, then goes into a chaotic, discordant two-minute lead viola part as the song climaxes. If you don’t mind handheld shakycam, there is a well-recorded live video of this song at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qFLw26BjDZs. Starting at about 1:44, for ten seconds or so you can see what Cale is actually doing. The cameraman was a lot more interested in Lou Reed and Nico than the rest of the group, though, so we don’t get to watch much more of Cale’s technique. Also on The Velvet Underground and Nico, there is a similar, lower viola drone runs through the verses—plus the last line of the chorus—of “Venus in Furs”, and Cale’s viola part on “The Black Angel’s Death Song” could easily have been written by Young, or by Philip Glass.

But to really parallel Weill, after leaving the Velvets, Cale would have had to start working with Stephen Sondheim, or have become a more serious Andrew Lloyd Webber. Before he turned to cabaret, Weill was a rising star of the classical world: at 15 he publicly performed original lieder; he directed operas, composed choral works and orchestral works including symphonies, a fully orchestrated divertimento, and the music for a children’s pantomime performed at the Theater am Kurfürstendamm. At the same time, he was earning money playing piano in a basement Bierkeller and teaching music theory and composition to private students, several of whom (including the American Esther Zweig) went on to be important figures in classical music in their own right. Then, much as Cale took a sharp turn in working with Lou Reed, he took an equally sharp turn in moving into the cabaret scene, eventually collaborating for several years (1928-1930) with Bertolt Brecht and—she never gets the credit she deserves—Elisabeth Hauptmann on work that stands up as well as the Velvets’. With the rise of the Nazis, he fled Germany and bounced around Europe a bit, going back to a more classical sound for a few years (including Seven Deadly Sins, his last major collaboration with Brecht) and then to the U.S. In the remaining 15 years of his short life he became a major Broadway composer (one of the few in that era to do his own orchestrations) and a proud American citizen. Among the lyricists he worked with were Maxwell Anderson, Ira Gershwin, Langston Hughes, Oscar Hammerstein (on one WWII propaganda song), Alan Lerner, and Ogden Nash. About the only thing those people had in common: they wrote well, and they worked with Kurt Weill.

I don’t want to push the analogy too far: unlike Cale, Weill never entirely left behind the more classical world. His Down in the Valley with librettist Arnold Sundgaard (originally a short 1945 piece for radio, later a full 1948 opera) is almost exactly in Aaron Copland territory, reworking American folk songs in a more classical context, and Street Scene (1946, book by Elmer Rice, lyrics by Langston Hughes) is probably the closest Broadway ever came to producing an opera (yes, I am aware of Porgy and Bess, and I stand by what I just said).

We’ll never know what Weill would have thought of Cale, because Cale was only eight years old when Weill died of a sudden heart attack in 1950 and, oddly, unlike his colleague Lou Reed, Cale has never to my knowledge covered a Kurt Weill song.

Joe Mabel

More info:

https://www.facebook.com/groups/299892691477483