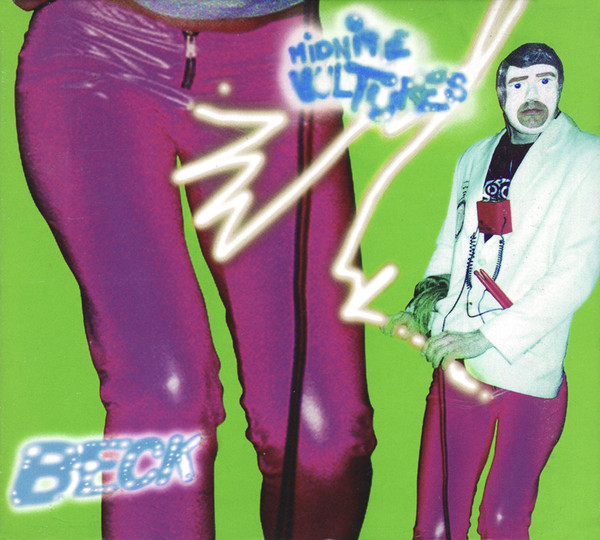

[Editor’s note: Below you will find a review of Beck’s Midnight Vultures written by Tom Fredrickson on December 6, 1999 for Pandemonium Online. Upon recent listens, the author has found that Midnight Vultures “holds up and sounds better than ever on the sound system mine has grown into.” Thus, to celebrate one of Beck’s finer legacy albums, we present you with this trenchant review, updated with two Youtubes. Fredrickson adds that these “videos do absolutely nothing to quiet the reservations I raise in the review.” He further would like you to know that “Sexx Laws features a cameo from Jack Black and represents well the mannerist phase of the MTV video age.” ]

One of my prized musical possessions is an LP called Souled Out, released by K-Tel circa 1975. This compilation of one-hit wonders, no-hit blunders, hidden gems (George McRae’s “I Can’t Leave You Alone” is even better than “Rock Your Baby”) and R&B landmarks gave even me, the whitest boy on the block, entree into the exotic world of funk and soul.

The seductive cross-section of styles on Souled Out lives on in Beck’s Midnite Vultures, which is a slice-and-dice tour of the last 30 years of African American pop: from the staccato horn accents, wah-wah guitars, and gurgling clavinets of high-sheen soul to the creepy busted gamelan sonics of mid-80s hip hop to the declamatory rhymes of rap. This tour de style has enough hooks per minute to satisfy the staunchest old school fanatic and makes Midnite Vultures the most immediate and immediately enjoyable Beck album yet.

Beck being Beck, however, this is not merely a genre exercise. Typically Beckian lyrics keep things off-kilter throughout. (My favorite but by no means the strangest or funniest line is, “You look good in that sweater and that aluminum crutch.”) But it’s the music — as opposed to the concepts, ironies, or beats — that consistently surprises. When the banjo and pedal steel drop from out of nowhere into the middle of “Sexx Laws,” Beck finds a way to fit them seamlessly into the mix. And the celestial choir that drifts into “Get Real Paid” feels like the perfect counterpoint to the weird white boy technofunk of that song. These jump cuts don’t seem like cheap jokes (something I’ve accused Beck of in the past) so much as epiphanies, unforeseen but in retrospect perfect.

The plentiful musical ideas on Midnite Vultures means that these songs take you on unexpected journeys. The druggy Sly Stone bass riff that opens “Nicotine & Gravy” inspires three or four successive vocal lines, which Beck eventually stacks up like a fugue before Arabic-sounding synth lines lead the song off in a whole new direction. This is the most meticulously crafted record of Beck’s career, and it’s also one hell of a lot of fun.

The momentum and confidence of the album are impressive. Barely a sound seems out of place — the most surprising of which is Beck’s voice. Think of vocals on past Beck records and you’ll probably call up that utterly affectless drawl of his — or maybe that inhuman vocorder rallying cry, “Two turntables and a microphone.” On Midnite Vultures Beck leaps into a whole new range — literally — by adopting an expressive falsetto that bridges the gap between Eugene Record of the Chi-Lites and Prince. Like generations of white men before him, Beck has found something in black music that allows him to say things — and say them in a way — that he isn’t be able to otherwise. Beck seems to have discovered a new kind of joy, sexiness, even tenderness in his music.

But things get complicated when the white boy blacks it up — even if it’s Beck, whose previous embrace of the blues, if somewhat dutiful, is well established. The line between homage and parody in music is a thin one, and it’s reasonable to ask if Beck crosses it in songs where he boasts of “packin’ heat” or what exactly he’s up to with choruses thrown out in his best ghetto drawl. In one way the album closing “Debra” is Midnite Vultures’s most impressive cut: a full-blown soul melodrama worthy of the Stylistics. And yet it’s also the most troubling cut, with Beck sounding like no one so much as Mick Jagger doing his best ironic-cum-sincere minstrel falsetto. With Midnite Vultures Beck enters the house of mirrors where race meets culture, and if it says nothing else, the album makes it clear that our most vital music continues to pick at the bones of the blues.