With World Whiskey Day occurring last week, this seems like a good time to look at a (very) abbreviated history of the spirit.

Residue from a beer-like fermented drink was recently found in stone vessels in Raqefet Cave in Israel that is thought to be 13,000 years old. Remnants of seven different plant types, including wheat/barley, oat, legumes, and flax fibers were identified in fiber-made containers and stored in boulder mortars. This is significant, as it places the first evidence of actual alcohol fabrication several millennia prior to the domestication of cereals and grains 10,000 years ago. This raises the question of whether humans transitioned from nomads to inhabitants of cities to supply them with the available raw materials for making alcohol.

These crude beer-like ‘drinks’ were created by groups of people chewing the grains then spitting them into a pot where they were allowed to sit and ferment. Once fermented – likely in the 2 to 3% alcohol range – the group would sit around the pot with long straws made from reeds, which allowed them to get down below grain into the fermented liquid, drinking what some have called a bread milkshake.

The natural fermentation process ends as the alcohol content (Alcohol by Volume, or ABV) reaches somewhere below 15% – depending on the yeast and sugars present. At that point, the yeast is no longer able to metabolize the sugars, and the fermentation ends. Only by distillation can this percentage be increased. Prehistoric Akkadian tablets provide evidence of the distillation of liquids into their base components by the Babylonians in 1200 BC for use in perfumes. The ancient Egyptians, inhabitants of the Indian sub-continent, and China were all beginning to distill liquids within the first several centuries AD. But the first real evidence of the distillation of alcohol comes from the Arab chemist Al-Kindi in the Ninth Century in what is now Iraq. Distillation was primarily to produce perfumes, as alcohol was found to be very good at stripping away the essence of botanicals. There is also evidence of Arab alchemists distilling grapes to make medicine in the Eighth Century.

Irish monks began distilling whiskey in the 12th Century for the purpose of medicinal consumption, after bringing the technique of distilling perfumes back from the Mediterranean. Ironically, the first mention of whiskey in print comes from 1405 in the ‘Annals of Clonmacnoise,’ where it was written that the head of a clan died after “taking a surfeit of aqua vitae (ethanol)”. So, the first written mention of whiskey is also its first recorded death from the substance. This whiskey would have been distilled from crude beer, resulting in a liquid that is nothing like what we consider whiskey today. The Irish also gave us the name for this new spirit. ‘Usquebaugh’ is the Gaelic word for ‘aqua vite’, which was bastardized over time to the word ‘whiskey’ we use today.

Monks started by adding medicinal herbs such as mint, thyme, and anise to make the spirit more palatable. Largely unregulated for hundreds of years, the first license was granted by King George I to Sir Thomas Phillips in 1608, and this license is thought to be the original license that is now held by the Old Bushmills Distillery. In 1831 Irishman Aeneas Coffey invented the column still, allowing much higher production and smoother spirits, but it wasn’t until the French Cognac trade was decimated by the phylloxera aphid beginning in the 1850s, that whiskey became an international spirit.

Irish whiskey is produced without the use of peat, a staple in the production of Scotch. It was typically distilled and aged next to the sea for transportations reasons, but the consistent weather due to the adjacent body of water produced a smooth finish, making it highly desirable. Since the sun never set on the British Empire at the time, Irish Whiskey was transported across the globe, making it by far the highest selling spirit in the world. It maintained that position until the end of the second decade of the Twentieth Century. A combination of WWI (1917-1919), the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921), and Prohibition in the US (1920-1933), brought the industry to its knees, falling to only 5% of the worldwide consumption. With the British and the Americans no longer purchasing the spirit, most of the distilleries either shuttered or were purchased by the ones still surviving.

The Irish Maid

2oz Irish whiskey

1/2oz St. Germain elderflower liqueur

3/4oz fresh lemon juice

3/4oz simple syrup

2 – 1/4″ thick cucumber slices

Cucumber slice garnish

Muddle the cucumber slices in a shaker, then add the remaining ingredients. Fill with ice and shake for 15 seconds. Double (for sure double) strain into a double rocks glass over ice. Add the garnish and serve.

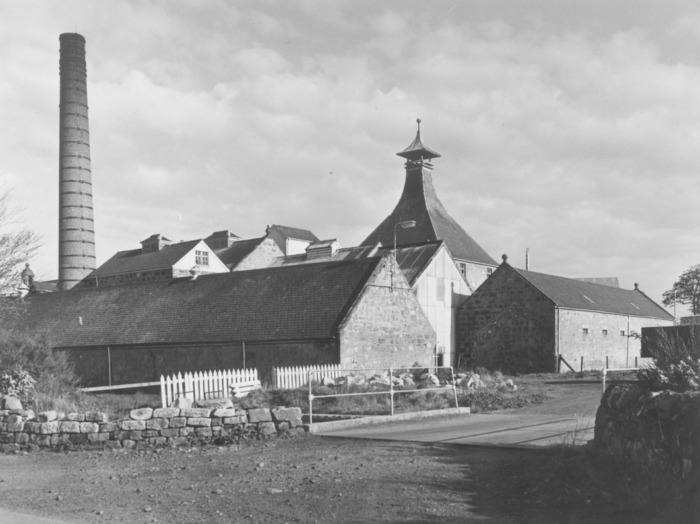

Scotch, starting later and in very small distilleries, was virtually unknown outside Scotland until well into the 1800s, but they took the unpredictable and rough spirit and began blending it to produce consistent output. The first mention of Scotch Whisky is from 1494, and its production began to be taxed in 1644, pushing much of the production underground in unregulated distilleries. The first licensed distillery was in 1824 by the Glenlivet Distillery.

The lands of Scotland have been covered in bogs for thousands of years, and peat from these bogs has historically been the primary source of fuel in the country. In the distillation process, the peat is burned to dry the malted barley. The smoke from the burning peat gives peated scotch its distinctive smokey flavor, and the length and intensity of that smoke its related to the strength of the flavor. While not all Scotch is peated today, with no other available source of fuel, for hundreds of years it was the only scotch available.

There are five regions of scotch production: Campbeltown, the Highlands, Islay, the Lowlands, and Speyside. It’s a bad idea to categorize or summarize scotch in simple terms, but in general, scotch produced on the rocky island of Islay (‘eye-luh’) off the southeast coast of Scotland – basically a large peat covered rock – tends to be the smokiest, with a medicinal iodine taste. Love it or hate it, you know an Islay scotch well before it touches your lips. On the opposite side of the spectrum sits Speyside, the largest collection of scotch distilleries in the world; 49 distilleries straddling the Spey River. Speyside scotch tends to have little peat and more fruit undertones. And literally everything in between on the other three regions.

Scotch was primarily blended until the middle of the last century when distilling technology allowed refinement of the spirit. Today we have Single Malt (the most popular scotch in American homes), and Single Grain, in addition to blended varieties.

The Rob Roy

2oz Scotch whiskey

1oz sweet vermouth

2 dashes Angostura Bitters

Luxardo cherry garnish

Add everything to a mixing glass filled with ice. Stir for 30 seconds, then strain into a chilled cocktail glass. Add garnish and serve.

In Colonial America, whiskey was just getting started. If any spirit fueled the Revolution, it was rum. Some inventive African slaves in the Caribbean realized that molasses, an industrial waste from the production of sugar from sugar cane, could be fermented and distilled into a barely drinkable alcoholic spirit. It grew and grew in popularity in the New World, with an almost endless supply of raw material that otherwise was literally being dumped into the ocean. But once the Revolutionary War was over, cheap and easy access to the spirit and/or raw materials from the British controlled island neighbors to the south became very expensive. But luckily the Colonists had been growing grains for centuries. Barley did not do so well in Colonial America. But rye did.

Some of the earliest letters written from the colonies include reports on distillation. In the fall of 1620, Captain James Thorpe wrote from Virginia that he had successfully distilled alcohol from the native corn. This is the first instance of whiskey being distilled from corn, making Thorpe the father of all corn-based moonshine and bourbon whiskey. In a letter dated December 19, 1620 to his distillation partner John Smyth, he writes that he had successfully distilled “some good drinke of Indian corne”. European grapes vines were brought over along with passengers, but most plants died quickly, forcing the new inhabitants to try literally everything they had around them – wild berries, pumpkins, apples, vegetables, and pears.

Thanks in part to the climate and soil, especially in Pennsylvania and Maryland, rye took off with Pittsburg the center of production. Corn could be eaten – so rye was available for making whiskey. Add Scottish and Irish immigrants who brought knowledge of distilling from their home countries, and the spirit was poised to lead the western expansion. Even George Washington, after completing his two terms as President, realized the potential. He had no experience in the production of spirits but did have a gristmill on the property and grains to use. He hired a Scottish immigrant to oversee the new construction and distillation of rye and corn at Mount Vernon. The year of his death in 1798, the distillery was producing 11,000 gallons of whiskey, equating to a large medium-sized distilling organization in today’s terms.

American Rye whiskey, which must use a minimum of 51% rye grain, is the spicier brother to the sweeter bourbon, made with a minimum of 51% corn. It dominated the next century both in quality and quantity, and it is likely that the first mention of the cocktail in 1903 in The Farmer’s Cabinet was made with rye. Rye went onto be the base spirit of most of the iconic cocktails we think about today; the Old Fashioned, the Manhattan, even the Sazerac, which was originally made with cognac until the phylloxera aphid invasion in France, became associated with rye. But this dominance was only temporary. The one-two punch of WWI and Prohibition following almost shuttered the industry. Some of the distilleries made it through to the other side, but by then it was its twin brother bourbon’s time to shine.

The Vieux Carré

1oz rye whiskey

1oz VS cognac

1oz sweet vermouth

1/4oz Bénédictine Liqueur

1 dash Angostura Bitters

1 dash Peychaud’s Bitters

Lemon twist

Add everything to a mixing glass with ice and stir for 20 seconds. Add ice to an Old-Fashioned glass and strain over the top. Express the lemon over the surface and serve.

Bourbon came into its own as a spirit primarily as a transportation issue. Just as the soil and climate in the mid-Atlantic states were perfect for rye, the same was true of the land west of the Appalachian Mountains for corn. The soil was so fertile that farmers didn’t know what to do with all their harvest. The Eire Canal was completed in 1821, making passage from the states on both sides of the mountain range easier to navigate, but corn was heavy, and the trip was long. While commercial distillation of corn whiskey has been around for a long time – the Evan Williams distillery was opened in 1783 in Louisville, KY – the majority of distillation was at the farm level for personal use and for trading with neighbors (water was still considered dangerous at the time, but alcohol was safe to drink).

Bourbon was given its name in 1840 when a distiller named Jacob Spears named his product Bourbon whiskey. Old Bourbon County whiskey had been around for decades and for many, this was the first Kentucky spirit they encountered, so the name already had value with consumers.

The bourbon of the day was not what we think of when we think of bourbon today. Many distillers took their product seriously, but most of it was unaged (unless sitting in a barrel on a wagon or ship during transportation was considered aging). It was inconsistent and could be harsh, only a few steps away from moonshine. Many distilleries turned to the Scottish practice of blending, mixing several different barrels together to create a more consistent and desired product.

But bourbon suffered the same struggles that rye did in the first three decades of the Twentieth Century. Some whiskey producers applied for and were awarded permits to produce ‘medicinal whiskey’ during prohibition, but most never made it through America’s Nobile Experiment. And unlike scotch whisky which gets better and mellower as it ages, bourbon has a lifespan in a barrel. After somewhere between 8 and 12 years the spirit takes on too much of the cask and can become very woody and unpleasant. Prohibition lasted 13 years, making the hundreds of millions of gallons of whiskey stored in rickhouses across the country worthless.

The Whiskey Daisy

2oz bourbon (or whiskey)

1oz fresh lemon juice

1/4oz simple syrup (or gum syrup)

1/2oz Grand Mariner

Fruit of the season garnish

Splash of soda water

Add everything (no soda water) to a shaker filled with ice and shake for 15 seconds. Double strain into a chilled coupe glass and add a splash of soda water (it doesn’t take much). Add garnish and serve.

But bourbon, and its twin Tennessee whiskey, benefited by a government program meant to help the farmers. Corn was subsidized by the US government following WWII, and it was plentiful. This begins the zenith of bourbon, while rye all but disappeared. It was short lived. The clear flavorless, odorless, vodka had found a foothold following the Second World War and after 1950 the share of vodka sold in America grew steadily as whiskey began to fall. In 1976 Vodka became the largest selling spirit in America, where it still sits today.

But vodka is not exactly a crafted spirit (adding flavor doesn’t change that fact). In the late 1990s America’s taste in spirit began to change again – although slowly at first. Enterprising bartenders who were tired of making large glasses of fruit juice and vodka drinks began looking back to old recipes and almost forgotten cocktails. Craft cocktail bars started popping up, first in London, then quickly followed by New York, and discerning drinkers lined up. Taking a que from the small niche craft beer breweries that had been popping up over the previous two decades, craft distilling came into its own. Sometimes it was an individual who wanted to make something special, and sometimes it was a bartender who approached an existing distillery to make small batches of distinctive (or older) spirits.

In the year 2000 there were 24 craft distilleries in the United States. By the end of 2011 that number had risen to 243. By 2019 that number had grown again to over 2,000, with production in all 50 states. And this exponential growth does not appear to be slowing. Most of this growth is in the bourbon, but rye – almost extinct – has come back with a vengeance. With its sharp and spicy profile, it has attracted attention of many distillers and mixologists in what it offered to the pallet.

So raise a glass to all those who toiled for centuries so you could argue with your drinking friends about whether rye or bourbon makes the best Old Fashioned.

Cheers!

Bill

AotCB-038

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail

Previously in Architecture of the Cocktail:

Architecture of the Cocktail: Ten Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Bourbon, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The True Story of Jack Daniel’s Whiskey, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: World Whisky Day. A Brief History of Whisk(e)y?, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The Japanese Whisky and the Highball, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The Delicious Dozen, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: What makes a cocktail, a cocktail? by Bill Stott