With National Bourbon Day occurring last week, it seems like a good time to take a deep dive into “America’s Native Spirit.”

- Bourbon is one of the first distilled spirits in the New World

Well, the term bourbon may be a bit of a stretch, but the early settlers needed something safe to drink, and for far longer than recorded history mankind has known that fermented liquids were safer to drink than local water. Settlers, purists, pilgrims, and colonists brought grape vines and barley with them, but both were unable to survive the harsh North American climate. So, they fermented anything they could get their hands on – pumpkin, berries, grass, apples, and pears.

Some of the earliest letters written from the Colonies include reports on distillation. In the fall of 1620, Captain James Thorpe wrote from Virginia that he had successfully distilled alcohol from the native corn. This is the first recorded instance of whiskey being distilled from corn, making Thorpe the grandfather of all corn-based moonshine and bourbon whiskey. In a letter dated December 19, 1620, to his distillation partner John Smyth, he writes that he had successfully distilled “some good drinke of Indian corne”.

- Bourbon does not have to be made in Kentucky

There are a lot of rules about ‘America’s Native Spirit’. What it is made of, how and how long it is aged. But curiously one thing that is not spelled out is where or what region it must come from. Champagne must come from the Champagne region of France. Tequila must be made in the Mexican state of Jalisco (with a few exceptions). Bourbon must be made in the Unites States, but short of that it can be made from Maine to Hawaii. 95% of all bourbon is made in Kentucky, but surprisingly from the beginning of Prohibition up until 2014 there were no active bourbon operations in Bourbon County, Kentucky. That year a small craft distillery, Hartfield & Co. opened in Paris, Kentucky, the county seat.

- Bourbon must be made with a minimum of 51% corn

Bourbon must be made with a mash consisting of at least 51% corn (American rye must be 51% rye grain). It is typically made with a ratio of 65-75% corn, 10-20% rye, and 5-15% barley. It can be made with 100% corn, and if it is unaged or aged in an un-charred barrel it is simply corn whiskey. Once it is placed in a charred oak barrel and aged for at least three months, it becomes bourbon. Wheated bourbon on the other hand, swaps out wheat for the rye, resulting in a smoother, sweeter spirit (think Maker’s Mark, Pappy Van Winkle, and Weller). High-rye bourbon contains up to 40% rye, for a spicier, richer bourbon (Four Roses, Bullet, and Old Forester).

- Unaged bourbon is called White Dog

Bourbon right out of the still is referred to as White Dog but goes by a number of other names – white lightning, light whiskey, white whiskey, or informally by moonshiners as hooch. It is colorless and gets nothing imparted by the barrel, remaining harsh. Many distilleries, notably Buffalo Trace, have begun marketing White Dog, but with bourbon gaining the majority of its benefits from its time in the barrel, it’s hard to understand why this is an attractive alternative. Some offerings are corn sweet, and include spices that would be lost during aging – but still.

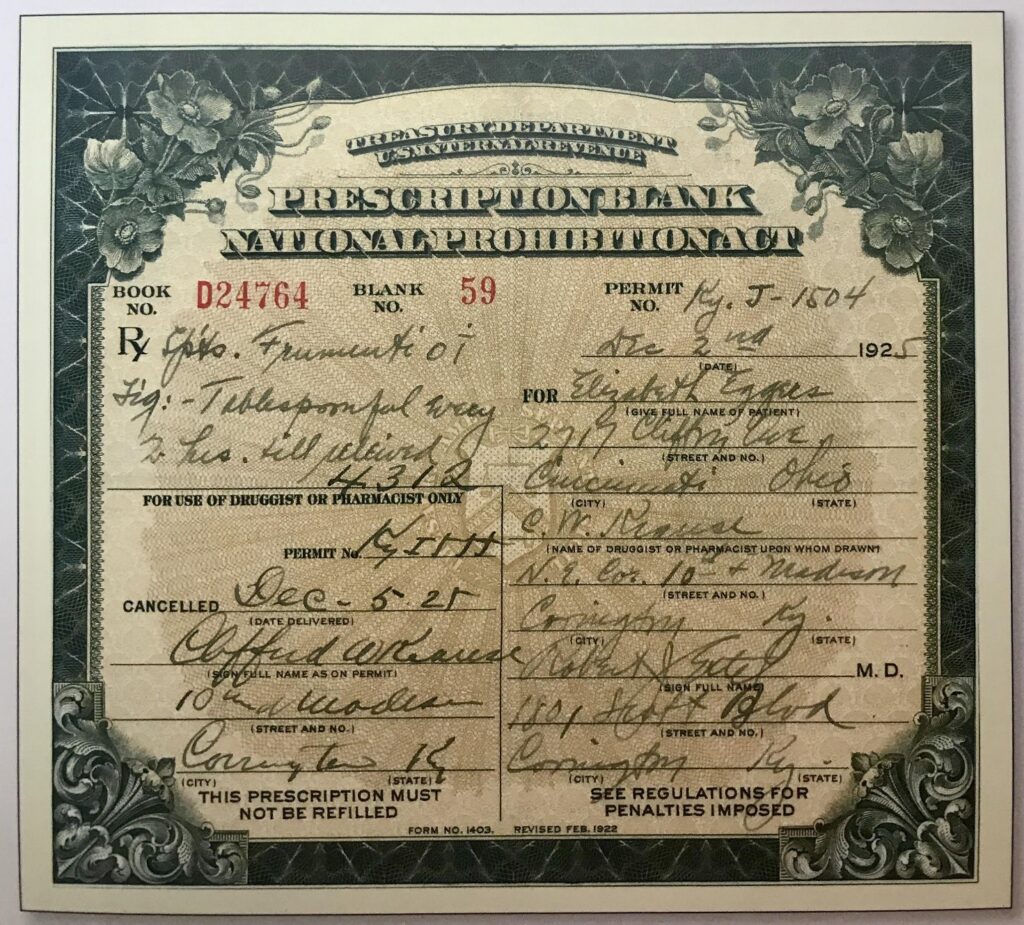

- Bourbon could be dispensed as medicine during Prohibition if you had a prescription

Many distilleries during Prohibition were shuttered, but others were converted to making industrial alcohol or medicine. But some were lucky enough to be licensed to sell medicinal bourbon (in reality – just bourbon). In 1916, the American Medical Association (AMA) stated that the benefits of alcohol for medicinal purposes was completely unsubstantiated. “Its use in therapeutics, as a tonic or a stimulant or as a food has no scientific basis”. This all changed after Prohibition was enacted, and doctors realized that they could make as much as $3 a prescription ($40 today). Suddenly entrepreneurial physicians were prescribing whiskey or bourbon for all sorts of ailments.

Drug stores got in on the money too, as a legal dispensary of medicinal spirits. Charles Walgreen founded his Walgreen’s drugstore in 1901, and by 1919 the chain had grown to 20 stores. But by 1929 the chain had grown to 525 locations – a 2500% increase – thanks to medicinal bourbon. The chain officially claims it was due to their soda fountains, but I’ll let you be the judge.

Six Kentucky distilleries held medical licenses during Prohibition: Brown-Forman, Glenmore, Frankfort Distilleries, Schenley, American Medicinal Spirits, and A. Ph. Stitzel. These distilleries could not produce new product but were allowed to sell from their existing inventories.

- Up to one third of bourbon disappears during the aging process

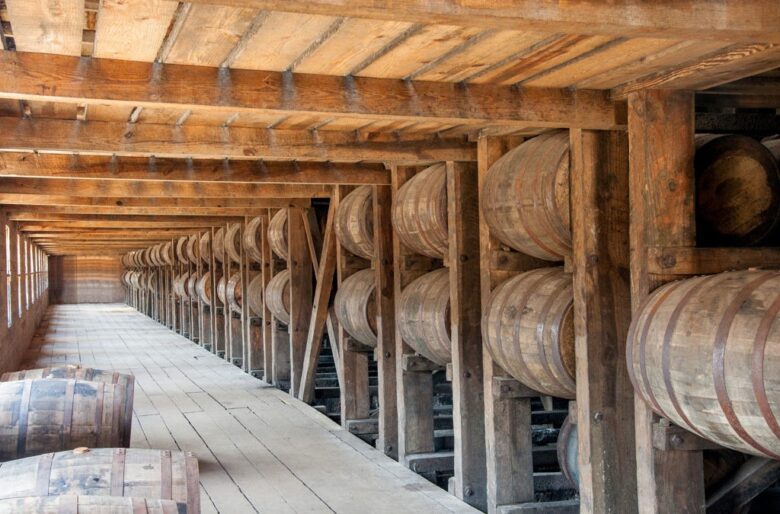

The term ‘Angel’s Share’ refers to the difference in the amount of spirit placed in a barrel versus the quantity present after maturation, or the amount of the spirit that evaporated into ‘the heavens.’ Every spirit aged in a wood barrel (scotch, cognac, wine, brandy, etc.) will lose volume during aging as the wood in the barrel swells and shrinks due to temperature and humidity. Scotland and Ireland have a relatively constant weather range due to being surrounded by water. In these countries the general rule is that 2% of volume is lost each year. Kentucky, on the other hand, has a more volatile climate, and loses approximately 4% of volume each year, with as much as 10% the first year. So, a barrel of bourbon aged 8 years can lose10% of its volume the first year plus another 4% more each of the remaining seven years.

Placement of the barrel within the rickhouse can affect the loss as well. Some rickhouses are up to nine stories high, with barrels stored on their sides on ricks (racks) three high per floor. The temperatures at the top of the building in the middle of the summer (most rickhouses are unconditioned) will be significantly hotter than those on the bottom. This causes the aging process to speed up – but also results in a much higher Angel’s Share.

- A bourbon barrel may be used only once

As decreed by Congress in 1954, bourbon must be aged in charred oak barrels, that may be used only once. The barrels are typically made from America White Oak that has been charred prior to placing the bourbon. That is where the requirement stops. Many distillers have been experimenting with multiple casks and even finishing in sherry, wine, rum, or cognac casks. Trey Zoeller, founder of Jefferson Bourbon, is always experimenting with casks, even going so far as to groove the interior surface (like a wavy potato chip) to increase the surface area prior to charring. Typically, the barrel is ignited by a propane flame until it catches fire, then burns at 500 to 600 degrees for as long as the distiller wants to create the end result they are looking for. Once the barrel is emptied, it is resold, often to Scotland where it is used to age scotch.

- There are almost 2 barrels of bourbon aging in Kentucky for every person in the state

In 2019 there were 8.5 million barrels of bourbon aging in the thousands of rickhouses across Kentucky. That year there were 4.5 million people living in the Bluegrass State. That is the highest number in over 50 when 9.1 million barrels were stored in 1968. The previous year? 1.9 million barrels in 1967.

- The name Bourbon comes from French Royalty

Bourbon is a uniquely America spirit, but its name is French. Bourbon comes from the name of a royal family in France, and the House of Bourbon was very powerful from the 1500s to the 1800s, responsible for several French Kings. The family had nothing to do with the distilling in America, but Francophile Thomas Jefferson, who preferred French wine to American hard spirits, is responsible for the name. After the Whiskey Rebellion of 1791, Jefferson, then Governor of Virginia, gave each Pennsylvania farmer 60 acres of land in what is now Kentucky (at the time it was still part of Virginia), if they agreed to build a structure and grow corn and produce “native corn,” or corn whiskey. He named the new region Bourbon County after the French dynasty.

- Aging bourbon is good. Over aging it is very bad.

We have become used to hearing about scotch that has been aged 10, 15, 18, or even 25 or 40 years. The longer the scotch stays in the barrel, the more mellow and flavorful it becomes. The same is not true of bourbon. Bourbon has no aging requirement and can be sold as bourbon after only three months in a charred barrel. Straight Bourbon must be aged at least two years. White Dog (unaged bourbon) has a complex flavor but has little or no smell and is transparent.

The charcoal on the interior surface absorbs some of the unpleasant flavors of the spirit (a process that can take up to three years), while the act of charring the barrel with heat releases flavor compounds otherwise locked within the wood. This is especially true of vanillin – which give some bourbon vanilla notes. The time in the barrel is what gives the bourbon its color as well.

However, unlike scotch, bourbon should not be aged in a barrel for more than 8-12 years. Once it hits its teens, the bourbon begins to leech out unpleasant flavors locked deep in the wood cask. Those flavors and chemicals become concentrated enough to spoil all that work. Unlike Scotland, where the climate is relatively even, Kentucky gets hot in the summer and cold in the winter, which expands and contracts the wood in the barrel. The barrels are stored in unheated rickhouses, and that expansion and contraction is constantly pushing and pulling the spirit deeper into the wood, pulling out flavors more quickly that in scotch. This is one of the reasons that a good master distiller is always moving barrels around from the top rick, the hottest place within the structure, to the bottom – or adjacent to an exterior wall to the middle of the rickhouse.

Can a super-aged bourbon still be good? Yes, but it is a gamble and requires a lot of TLC from the distiller. And even then, there is a point of diminishing return.

Cheers!

Bill

AotCB-041

Instagram@architecture_of_the_cocktail

Previously in Architecture of the Cocktail:

Architecture of the Cocktail: Ten Things You Probably Didn’t Know About Bourbon, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The True Story of Jack Daniel’s Whiskey, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: World Whisky Day. A Brief History of Whisk(e)y?, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The Japanese Whisky and the Highball, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: The Delicious Dozen, by Bill Stott

Architecture of the Cocktail: What makes a cocktail, a cocktail? by Bill Stott