In the mid ’60’s, my ex-girlfriend Antonia introduced me to the concept of “go” songs. These were the songs we heard on the radio that we had a powerful affinity for. Nowadays, you could say a “go” song is one you put on your iPod. Antonia and I tended to have the same ones, although on occasion, there would be a song I didn’t like at first that she did. I would always come around though. She tended to be quicker on the uptake than me. Sometimes it takes a song a while to grow on you. We would use “go” songs as oracles, among other things. If we had a yes/no question, and a “go” song came on while we were wondering, the answer was “yes.” Songs that were not “go” songs were mostly neutral, while songs we hated (“In the Year 2525,” “Me and You and a Dog Named Boo,” “You Light Up My Life“) were sort of “stop” songs. As oracles, of course, they indicated “no.” When I turn the radio on and it plays a “go” song, I feel the universe is giving me positive reinforcement. I know this is nuts and solipsistic, but it makes me feel good, and it doesn’t hurt anybody.

In the mid ’60’s, my ex-girlfriend Antonia introduced me to the concept of “go” songs. These were the songs we heard on the radio that we had a powerful affinity for. Nowadays, you could say a “go” song is one you put on your iPod. Antonia and I tended to have the same ones, although on occasion, there would be a song I didn’t like at first that she did. I would always come around though. She tended to be quicker on the uptake than me. Sometimes it takes a song a while to grow on you. We would use “go” songs as oracles, among other things. If we had a yes/no question, and a “go” song came on while we were wondering, the answer was “yes.” Songs that were not “go” songs were mostly neutral, while songs we hated (“In the Year 2525,” “Me and You and a Dog Named Boo,” “You Light Up My Life“) were sort of “stop” songs. As oracles, of course, they indicated “no.” When I turn the radio on and it plays a “go” song, I feel the universe is giving me positive reinforcement. I know this is nuts and solipsistic, but it makes me feel good, and it doesn’t hurt anybody.

But first, I’ll clarify something- my “go” song isn’t necessarily anyone else’s, and one of my “stop” songs might be someone else’s “go” song. Take, for example, Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Old Oak Tree, possibly the most wussy convict song ever written, and one that my wife, Betsy, and I both loathe. Betsy and her friend Marjorie were in a stadium in Scotland, witnessing the Edinborough Military Tattoo. The band played the dreaded “Yellow Ribbon,” which Marjorie hated as much as Betsy. The whole crowd not only sang along, but they swayed back and forth to the lame and dinky beat. Besides refraining from singing, Betsy and Marjorie refused to even sway along. Throughout the whole song, they got bump-bashed from the right, left, right, left… but the stalwart souls swayed not. However, the song has achieved iconic status, and is beloved by hundreds of millions. God bless human variety, I suppose.

Recently, I’ve thought of a new category, which I call “power songs.” These are songs of such force that they make the world a different place than it was before they were heard. On the scale of the universe, the difference would be slight to the point of being minuscule, but there would be a difference. I just thought, what about a “bad” power song, making a “bad” difference? Like what, “The Horst Wessel Song”? (Nazi anthem about an alleged Nazi martyr, actually a pimp and a petty crook, official song of, I believe, the Nazi Army). Well, there’s something to think about.

What got me on the idea of “power” songs was the result of meeting an old friend, Ed Ward, in Berlin (speaking of Nazis) in December of 2007. Jeffrey Lewis had lined up a gig for me at a program there about New York City. I was to represent the Greenwich Village folk scene in the ’60’s. Ed was the only person I knew in Berlin, so I went to see him. One of the first things he did was play me a song, saying this was one of the strangest things he’d ever heard in his life–this from someone who’s been writing about music since the ’60’s. He played the song. It sounded like a mix of doo-wop and reggae, recorded in 1960 or 61. But reggae was preceded by rocksteady and bluebeat, which were preceded by ska, which was preceded by mento. 1960/61 was about when the transition from mento to ska was taking place, way before reggae. WTF?

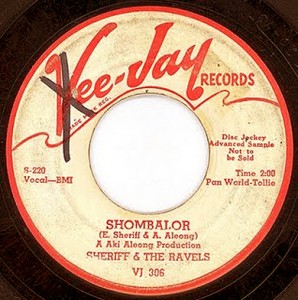

That, he explained, was “Shombalor,” by Sheriff and the Ravels, recorded in Brooklyn in December of 1958, and released on the VeeJay label. The track was on a four CD box set of VeeJay recordings that Rhino Records had just put out. Later research determined the song was written by Ravels singer Elmore Sheriff and Aki Aleong, a half-Chinese man from Trinidad, in 1955. The song was based on an African work song. The lyrics are:

That, he explained, was “Shombalor,” by Sheriff and the Ravels, recorded in Brooklyn in December of 1958, and released on the VeeJay label. The track was on a four CD box set of VeeJay recordings that Rhino Records had just put out. Later research determined the song was written by Ravels singer Elmore Sheriff and Aki Aleong, a half-Chinese man from Trinidad, in 1955. The song was based on an African work song. The lyrics are:

Go left, right, left, right

Go left, right, left, right

Go left, right, left, right

Go left, right, left, right (Oh lady) Shombalor, (Oh lady) Shombalor

Chickenin’ out and then a-root for it, chicken ‘n-a, Shombalor

Baby, d’y’wanna move out, do it now?

Ya getting’ on the countdown, please?

Baby, wha’ the fuck do you need, now? *

Ya getting’ on the catfish knees? ‘n-a

I love swing-ding

Rickey-bing, you’re a healthy one, hubba!

And it’s known to some that-a jigga-wah

I love pick-’em-up and lay-em-down

* (I know this was 1958, but it sure sounds like “fuck”)

(Oh lady) Shombalor, (Oh lady) Shombalor, (Oh lady)

Chickenin’ out and then a-root for it, chicken ‘n-a, Shombalor

And it’s gonna wine-o dine-o

Frees Jackie Frankenstein-oh

Maybe Jackie come to dine, ‘n-a

Forgettin’ on he stole my wine, ‘n-a

Asks George, “You bing, you bong, you bong?”

Jimmy Jones, he skipped to one, a-hubba

And it’s know to some that-a jigga-wah

I love pick-en-up and lay-’em-down

(Oh lady) Shombalor, (Oh lady) Shombalor (Oh lady)

Chickenin’ out and then a-root for it, chicken ‘n-a, Shombalor

Of all the animals in the world,

I’d rather be a bear (Raar!)

Climb the highest mountain,

Double to the rear.

(Oh lady) Shombalor, (Oh lady) Shombalor

Chickenin’ out and then a-root for it chicken in-a, Shombalor

I love fat man mambo,

Baby, do the king of the jungle,

You can only get it from the Congo

And you try to get it deftly

I love left foot stomp and-a right foot drag, ‘n-a

Hey, it’s good to march!

And it’s know to some that-a jigga-wah

I like pick-em’ up and lay-’em-down

(Oh lady) Shombalor, (Oh lady) Shombalor, (Oh lady)

Chickenin’ out and then a-rot for it, chicken in-a, Shombalor

Of all the animals in the world,

I’d rather be a bear (Raar!)

Climb the highest mountain,

Double to the rear.

(Oh lady) Shombalor, (Oh Lady) Shombalor, (Oh lady)

Chickenin’ out and then a-root for it chicken in-a, Shombalor

Go left, right, left, right [to fade, in a call-response duet with the lead singer]

How could I not possibly fall in love? Every once in a while, I come across a song I have to learn, and this was one for sure. I called in the Rhino/VeeJay box for a belated birthday present (thanks MaryLou!) and got to work. It took me several weeks before I could do the song justice, and for months, it rode through my mind, hour after hour. I welcomed every repetition. I see this song as the Rosetta Stone connecting African music, Caribbean music, and doo-wop.

I’ve had a long-standing theory about American pop music, which goes like this: there were two years that had a wide open, anything-can-happen aspect to them, musically speaking–1957 and 1966. Regarding 1957—first, rock and roll hit the mainstream all across the country in 1956, and by 1957 it was a vast, new, and ubiquitous force. Nobody had any idea just what it was, what it meant, or what to do about it, besides jump on the bandwagon or damn it as a force for evil. As a form, no one knew what the limits, if any, were. When the mighty spirit of “I don’t know” manifests, weird and wild possibilities tend to run rampant. I often think, what if 1957 could have gone on and on, growing in said weirdness and wildness? What stopped it, of course, was 1958—specifically, Chuck Berry and Jerry Lee Lewis being arrested, Elvis getting drafted, Little Richard renouncing rock and roll for the church, The Buddy Holly/Richie Valens/Big Bopper plane crash, along with the record industry’s introduction of a deluge of rockin’ teen twerps, most of whom were named Bobby. One of the few alpha rockers to escape said carnage was Ray Charles, who even rock haters had to acknowledge as a genius. The label “soul music” was originally coined so the music of Ray Charles could have another label besides rock and roll, which to most people back then meant trash.

Getting back to the Rosetta Stone, Harry Belafonte’s Calypso album came out in 1956, and by ’57, there was a full-blown calypso craze as well. However, there weren’t many r&r/calypso mergings. Chuck Berry’s beautiful “Havana Moon” is one of the very few. Both rock and roll and calypso, of course, can be traced back to Africa, which brings us back to “Shombalor,” the only rock/calypso/African hybrid from back then that comes to mind. For years, I’ve been thinking of trying to write some let’s-pretend-it’s-1957 songs in an effort to attempt to capture the goofy and beautiful spirit of the time.

If you want to get a feeling for that singular year, one of the best ways it to check out the 1957 cars. The ’57 Chevy is the most iconic example. Some call it the most beautiful mass-produced artifact ever. Personally, I thought the ’57 Plymouth (the one in Steven King‘s Christine) was prettier. But the 1957 cars were absolutely glorious, and they gave that year a magical glow.

If you want to get a feeling for that singular year, one of the best ways it to check out the 1957 cars. The ’57 Chevy is the most iconic example. Some call it the most beautiful mass-produced artifact ever. Personally, I thought the ’57 Plymouth (the one in Steven King‘s Christine) was prettier. But the 1957 cars were absolutely glorious, and they gave that year a magical glow.

A few months ago, my wife and I went to New York’s Pier Antique Show, and I spent an hour at a paper goods booth looking through old copies of Hit Parader magazine, which mainly features song lyrics. I was trying to find a song called “Billy” (‘Billy, Billy, Billy, Billy, cross over the bamboo field,’ a simple, haunting song I hadn’t heard since 1957), which turned up in the August 1957 issue. I bought three different 1957 Hit Paraders. If you want goofy, try this refrain from “Yes Tonight, Josephine“:

Yip! yip! bop do boom diddy

boom diddy

Yip! yip! whip bop de boom!

Or, from “Shish-Kabob Rock“:

Rock! a-rock! a-rock-a-ya ha-yu-nee!

Roll! a-roll! a-roll-a-ya ha-bee-bee!

Not to mention Gene Vincent‘s “Be-Bi-Bicky-Bi-Bo-Bo-Go.”

But since hearing “Shombalor,” I’ve been thinking of the African/Caribbean/Doo-Wop consolidation, and trying to write from that nexus. It seems really simple, but I haven’t managed to start one yet. It’ll come.

I just noticed another thing about 1957— punk was an effort, among other things, to get back to simple, basic, pure rock and roll. What punk wanted to do was go back, in a nutshell, to 1957. Only with a potty mouth. I’m now working out a bunch of 1957 songs as an exercise in total immersion. I’m also finally learning to finger-pick the guitar, and am trying to finger-pick the 1957 songs whenever possible. My tentative first composition in this style, which I don’t know if I can pull off, will be “Fuck You, You Fucking Fuck,” an astounding sentence I got off a T-shirt on Bleecker Street in Greenwich Village in the ’90’s. Adding this a few weeks later, I wrote the song, but it turned out to be on banjo. Writing potty-mouth 1957 songs in the approximate style of Uncle Dave Macon is a sub-genre that hadn’t occurred to me, but it sure has now.

Besides writing some 1957 songs, some 1966 songs, some early 60s R&B songs, and some ’30’s/’40’s style pop songs (I haven’t done any yet), for the last several decades I’ve been intending to actually practice, or more accurately, play music every day. One of our band members, Jeannie Scofield, was getting married last August, and she asked me to play at her wedding. She chose ten songs from between 1901 and 1945, along with the standard Wagner and Mendelssohn wedding classic instrumentals. Her father is the brilliant jazz guitarist John Scofield, and between the two of them, I wanted to do the best job I possibly could. So I played every day for two weeks, and thought, “hey! I’ve been playing every day for two weeks! All I have to do is keep it up and an objective I’ve had for decades will have been reached.” This time I actually kept at it, and have recently passed day 250.

After the wedding, I started playing guitar, fiddle, and banjo every day, beginning with “Shombalor,” which I had been thinking of as a Power Song. For my fiddle practice, I played fiddle tunes from the Harry Smith Anthology, along with a mid 20th century fiddle tune called “Crazy Creek,” ‘power’ songs, or tunes since they have no words. Anthology fiddle tunes “Indian War Whoop,” “Wake Up Jacob,” “Brilliancy Medley” and “La Danseuse” are ‘power’ tunes for sure.

To compound the weird coincidences, I recently found a site called Old Weird America, which is dedicated to the Smith Anthology. When I looked up Eck Robertson, who played “Brilliancy Medley,” there was a link to the Fairport Convention’s video of their version. Now, “Brilliancy Medley” and “Crazy Creek” are two of the main tunes I’m working on. When I played the “Brilliancy Medley” video, I found it concluded with them playing “Crazy Creek.”

But I found that when I had time to play just one instrument, I would go for the banjo. It was just more enjoyable to fool around with. Then a few months ago, I met some people who wanted to try some banjo on the sound track of a movie. One scene called for a folky instrumental, and I played a tune called “Monday Morning” that I learned from a Peggy Seeger record in—Good Lord!—1957! It was in C modal tuning (D, C, G, C, G), and was the only song in that tuning that I ever played. I decided to try making up a tune in that tuning, so if they used me, I’d have a composition credit. I had no idea at the time that I would become totally captivated, and spend the next several months mostly playing in this tuning.

I learned how much could be done with just one string when I saw the Singers and Dancers of Sierra Leone at the New York World’s Fair in 1964. The Sierra Leone exhibit had a little stage on the outside where they did a ballyhoo-style teaser for the big show. There was a short old guy playing a one-string violin-like instrument, and another, bigger old guy, who they said was the leader of the dancers. The barker said the dancer was going to dance while holding a 300-pound drum off the ground. I was with Antonia, and Steve Weber, my music partner in the Holy Modal Rounders. We all decided this was something we had to see. I just remember two things from the show. First, the guy who played the one-string fiddle-like instrument (using a western style bow) sounded better than just about any fiddle/violin player I’d ever heard in my life. Using just one string. I hadn’t thought it was possible to do that much with just one string. That’s when I learned otherwise.

But the most amazing thing was the dancer, who like the fiddler, appeared to be in his ’60’s. The audience was invited to inspect the 300-pound drum he would allegedly lift off the ground while dancing. The drum was about 5 feet tall, and had a yoke-like structure on the top. Several people, Weber, and I, tilted the drum on its side to check the weight. It was definitely too heavy for any of us to lift. 300 pounds sounded about right. We went back to our seats, and the music started. The dancer spread his arms wide, and started dancing very slowly, leaning back a little and rocking slightly from side to side, while turning slowly around and around in wide circles. He did this for several minutes before finally approaching the drum, continuing the slow, deliberate, and unchanging dance he had been doing. Then, arms still outstretched, he bent over, putting his head through the yoke-like structure on top of the drum. Then he slowly arched his back. The drum rose from the ground. The dancer resumed the same “dance” he had been doing before he picked up the drum. Only now the drum was clearly off the ground. This continued for several minutes, going round and round, before he slowly lowered the drum to the ground, ending the dance. It remains one of the most amazing things I have ever witnessed. And to this day, I wonder, how in the hell? The guy had super powerful qi? The ability to do the uncanny through some mysterious use of rhythm? Voodoo?

I recently learned something else about the use of one string. For years, I have been puzzled by the guitar playing of Django Reinhardt. Specifically, how did he do it with only 3 functioning fingers on his left hand, the one that has to deal with the hard part of the guitar, the neck? How could he make chords with only 3 fingers? My friend John Parrott explained that his left hand went up and down the neck, like I had to do to make up tunes with just one string. I’ve since made up 5 tunes using mainly just one string and the drone (G), so I was more than ready to make up a tune in a different tuning.

All charged up with a fine new task, I quickly made up a new tune in this tuning. But I hadn’t expected to find the tuning so compelling. Practicing three instruments every day became fool-around-with-C modal tuning every day. So far, I have 6 new C modal tunes, all based on going up and down the neck.

A surprising thing happened a few months ago. I went to a picking party downtown, where there were a couple dozen people playing music. My idea was to have other people play along with my new instrumentals, but there were a number of banjo players, and they started playing in the key of A, which meant they had to put a capo on the 2nd fret and play in G tuning. I figured, what the hell, I’ll just stay in the “wrong” tuning. But I could easily play along in the key of A, and it sounded great. Does this have any meaning for a non-banjo player? Follow-up attempts to use this tuning to play along with other banjo players in different keys were not very successful.

The weird coincidences continue apace. I haven’t been naming these banjo tunes, but wanted to give them some theme, like stomp or breakdown, which would conclude the name, as in “Georgia Stomp” or “Earl’s Breakdown.” I finally decided on ‘Frolic.’ I had one of the C modal tunes I put words to, leaving five. Then Paul Lovelace, one of the film-makers who did the Holy Modal Rounder documentary, Bound To Lose, asked me to contribute to. OK, time for another coincidence. He was filming some friends and I on Bob Fass‘s radio program on WBAI, ‘Radio Unnameable.’ Bob has been doing this program since the early ’60’s, and it marked the invention and birth of free-form radio, mixing music of all kinds and periods together for the first time on one program. Paul and his wife Jessica then decided that their next documentary would be about Bob Fass- an excellent and brilliant idea. They went to an online site called Kickstart, which helps artists fund projects. He asked a couple of other musicians and I to help put together a bunch of stuff to give in exchange for a donation. He asked for five packages, and I had these five nameless tunes hanging around, so I suggested that donaters could have there very own name on a tune— they’d all be frolics, so if the person was Kurtzman it would be “Kurtzman’s Frolic.” I got that idea because I read about a musician on Kickstart offering to use the name of the patron in the name of a piece of music in exchange for a donation. See kck.st/95usWL

The weird coincidences continue apace. I haven’t been naming these banjo tunes, but wanted to give them some theme, like stomp or breakdown, which would conclude the name, as in “Georgia Stomp” or “Earl’s Breakdown.” I finally decided on ‘Frolic.’ I had one of the C modal tunes I put words to, leaving five. Then Paul Lovelace, one of the film-makers who did the Holy Modal Rounder documentary, Bound To Lose, asked me to contribute to. OK, time for another coincidence. He was filming some friends and I on Bob Fass‘s radio program on WBAI, ‘Radio Unnameable.’ Bob has been doing this program since the early ’60’s, and it marked the invention and birth of free-form radio, mixing music of all kinds and periods together for the first time on one program. Paul and his wife Jessica then decided that their next documentary would be about Bob Fass- an excellent and brilliant idea. They went to an online site called Kickstart, which helps artists fund projects. He asked a couple of other musicians and I to help put together a bunch of stuff to give in exchange for a donation. He asked for five packages, and I had these five nameless tunes hanging around, so I suggested that donaters could have there very own name on a tune— they’d all be frolics, so if the person was Kurtzman it would be “Kurtzman’s Frolic.” I got that idea because I read about a musician on Kickstart offering to use the name of the patron in the name of a piece of music in exchange for a donation. See kck.st/95usWL

But to kick the coincidences further along, Paul asked that I would choose songs for a mix CD, asking for something like “all-time favorites.” Of course, I thought, “Power songs!” By this time, I had refined the definition to: a song or tune that has changed your life, or in the case of the following music, my life. What I have so far is “Beck’s Bolero” (Beck, Page and the Yardbirds), “Holiday For Strings” (David Rose), “Let’s Do The Boston Monkey” (Les Cooper and the Soul Rockers), “Friday On My Mind” (The Easybeats), the shape note song “All Is Well,” “Penguins” (Michael Hurley), “The Wind” (Diablos), “Waterloo Sunset” (The Kinks), “Sunspots” (Paul Whiteman Orchestra), a track by the Dezurik Sisters (world’s greatest yodelers, ever), “19th Nervous Breakdown” (Rolling Stones), “Dogs,” “I’m A Boy,” “Rael” (The Who), “Banjolina” (Doug Dillard), “Expecting To Fly” (Neil Young/Buffalo Springfield), “Sun Ain’t Gonna Shine Anymore” (Karen Dalton version), “Down in Mexico” (The Nutmegs), and “Temp-Tay-Shun” (Jo Stafford as Cinderella G. Stump).

OK, tons of other stuff has been going on, but I’m past my deadline. I’ll close off with a whistling update. I continue to whistle every day, and my inhale-whistling is getting as strong as my exhale-whistling. One of my ongoing projects is recording a song for each year of the 20th century. I’ll be finishing the first 50 years in a few months, it will be released in two 50-year installments. I’m considering adding period jingle/singing commercials for the period from the 1930’s to the 1960’s, and have been working some out. Upon doing this, I’ve been noticing how many of them feature whistling.

I’ll also close on a scary note. A few weeks ago, I was walking our dog around 2 in the morning after I had been working on music. My melodic head was in fine shape, and I was improvising particularly nice whistling melodies as I walked Stella. She started her going-in-circles-I-think-I’m-going-to-poop phase while I continued to whistle. Suddenly, I was slapped, hard, on my face by someone I hadn’t even seen approaching. I looked up, and there was this big guy, about 6 foot 3, who proceeded to yell at me incoherently, something along the order of ‘what do you think you’re doing, how dare you, stop that right now.’ Every New Yorker’s nightmare, attacked by a big crazy stranger on the street at night with no one in sight. Whatever the hell he was yelling, it was obvious that any attempt at conversation would be hopeless. I walked away rapidly as he continued his tirade, without looking back. He seemed to be following me. I turned the corner (Wooster and Grand, a location where I had taken two falls on ice, had a car accident when another car ran a red light, and where a building had suffered a partial collapse—bad feng shei central)—and ran into a neighborhood friend who was also walking his dog. At that point I looked back, and didn’t see the guy. He suggested calling 911, which I did. This guy’s removal from the street seemed like a pretty good idea. The cops came and drove around, but didn’t find him. If you’re walking alone at night in New York and see a big scary guy approaching, I would suggest, don’t whistle.

I’ll also close on a scary note. A few weeks ago, I was walking our dog around 2 in the morning after I had been working on music. My melodic head was in fine shape, and I was improvising particularly nice whistling melodies as I walked Stella. She started her going-in-circles-I-think-I’m-going-to-poop phase while I continued to whistle. Suddenly, I was slapped, hard, on my face by someone I hadn’t even seen approaching. I looked up, and there was this big guy, about 6 foot 3, who proceeded to yell at me incoherently, something along the order of ‘what do you think you’re doing, how dare you, stop that right now.’ Every New Yorker’s nightmare, attacked by a big crazy stranger on the street at night with no one in sight. Whatever the hell he was yelling, it was obvious that any attempt at conversation would be hopeless. I walked away rapidly as he continued his tirade, without looking back. He seemed to be following me. I turned the corner (Wooster and Grand, a location where I had taken two falls on ice, had a car accident when another car ran a red light, and where a building had suffered a partial collapse—bad feng shei central)—and ran into a neighborhood friend who was also walking his dog. At that point I looked back, and didn’t see the guy. He suggested calling 911, which I did. This guy’s removal from the street seemed like a pretty good idea. The cops came and drove around, but didn’t find him. If you’re walking alone at night in New York and see a big scary guy approaching, I would suggest, don’t whistle.

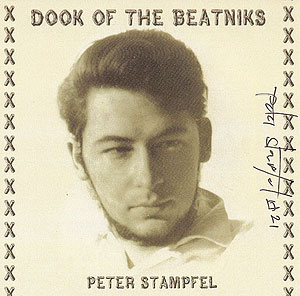

To end on a more upbeat note, My new CD, Dook of the Beatniks, came out recently. Signed and numbered copies are available for $15, which includes postage and handling:

Peter Stampfel

PO Box 223

New York NY 10014